Axial partners with great founders and inventors. We invest in early-stage life sciences companies often when they are no more than an idea. We are fanatical about helping the rare inventor who is compelled to build their own enduring business. If you or someone you know has a great idea or company in life sciences, Axial would be excited to get to know you and possibly invest in your vision and company . We are excited to be in business with you - email us at info@axialvc.com

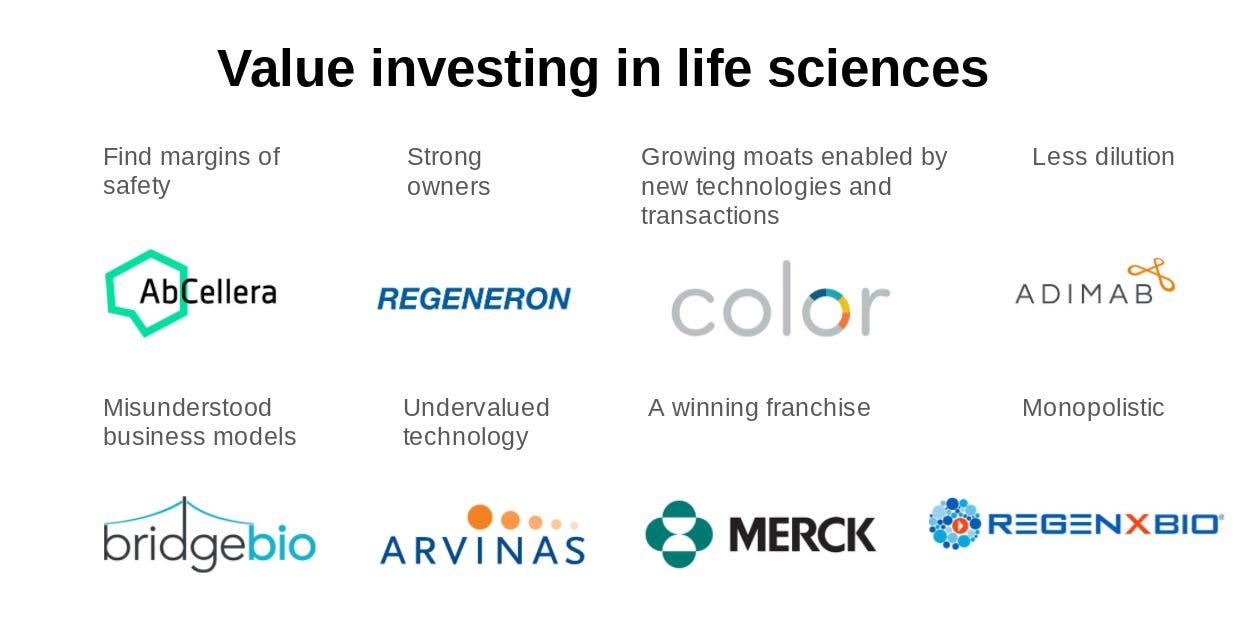

Value investing in life sciences

Is value investing possible in life sciences? This piece uses a set of case studies to show there is the potential to use ideas from value investing to identify and build great life sciences businesses.

Value investing is the practice of determining the intrinsic value of a business and investing at a price well below it. This leads to the next question - what is the intrinsic value of a life sciences company? Its patents? The fashionability of the company’s platform? The SAB? Common knowledge assumes that value investing in life sciences is more-or-less impossible because there’s too much technology risk. This leads to a common approach found particularly in biotech: invest based on momentum (i.e. what’s hot) and get in front of binary events (i.e. clinical trial readouts). This style doesn’t fit my personality and is just a little too risky. It’s like playing poker against Phil Ivey every day; I’d rather play against old college buddies.

A good part of value investing in life sciences means investing in great businesses. This is a tractable problem when compared to other styles. Great businesses have common features that can be analyzed. And case studies are pretty useful to distill these features. More often than not, many of these features are intangibles that are hard-to-value. Things like the founders, R&D capabilities, culture and mission, and more. There are challenges to figure out the real intrinsic value of a business in this field - many life sciences companies have negative cash flow early on and projecting future growth is pretty difficult. However, case studies of great life sciences businesses create models to figure out which companies have the potential to grow despite the early lack of profitability.

With a set of rules that make value investing possible and repeatable, the hard part about it is not knowing the rules or anything like that, it’s having the intellectual courage to come to your own conclusions. Excitedly, the Superinvestors of Life Sciences have shown it is possible over multiple decades to successfully invest in life sciences - https://axial.substack.com/p/the-superinvestors-of-life-sciences

Although I’m not here to tell all my secrets, it’s important to map out the key features of value investing in life sciences:

Find margins of safety

Strong owners

Growing moats enabled by new technologies and transactions

Less dilution

Misunderstood business models

Undervalued technology

A winning franchise

Monopolistic

Find margins of safety

A margin of safety is the ability to fail a few times without dying. In life sciences, this is usually enabled by several shots-on-goal. Whether they are financed by non-dilutive partnerships or through a large financing for a platform technology, the ability to fail is immensely valuable. Warren Buffett describes the concept very well:

“If you understood a business perfectly and the future of the business, you would need very little in the way of a margin of safety. So, the more vulnerable the business is, assuming you still want to invest in it, the larger margin of safety you’d need. If you’re driving a truck across a bridge that says it holds 10,000 pounds and you’ve got a 9,800 pound vehicle, if the bridge is 6 inches above the crevice it covers, you may feel okay; but if it’s over the Grand Canyon, you may feel you want a little larger margin of safety.”

In life sciences, the technology risk is so high that a margin of safety is a major prerequisite. AbCellera is a prime example of a business with a high margin of safety: they have a cash engine with its licensing business that empowers them to build an internal pipeline, have the capabilities to rapidly respond to something like COVID-19, and so much more. Another great example of a margin of safety in life sciences is finding some sort of hidden asset within a company. In drug development, it’s usually royalties on medicines - examples are Ligand Pharmaceuticals and XOMA.

Another example is working in a field with strong comparables ideally with well-funded trials/products or larger companies in the same field. Building or investing in a company with a unique approach in say NASH creates a margin of safety. While working on something like SCID makes the business risk a lot higher. Moreover, being part of a company that only has manufacturing risk instead of discovery creates a substantial margin of safety. Think Genentech and Amgen’s first products that were developed. Something similar is happening in synthetic biology with companies like Ginkgo Bioworks and Bolt Threads.

Strong owners

Strong founder-market fit is very valuable. Having company leadership be strong owners align their incentives with investors. A great example is Regeneron. It’s been over 30 years and the founders still lead the company. They have developed a string of transformative medicines generating over $7B in annual revenue with a valuation above $70B. And it seems the best is yet to come.

Often companies with strong owners non-intuitively don’t get the attention they deserve. Good owners always make sure to have ample cash and are obsessive about ensuring they partner with the best. That means they are not always on the fundraising circuit or getting a lot of attention from analysts. A well-operated business doesn’t really need the services of bankers or middlemen. This leads to a phenomena where these types of businesses are not as hyped up by the investment community.

Growing moats enabled by new technologies and transactions

Every company starts off very vulnerable. Their idea can be copied. They fail to raise sufficient capital. The market could be a mirage. And so much more. Great founders and businesses focus on growing their moats overtime to make sure they endure.

Every great and enduring business needs to pursue a valuable market - whether it's large and worth billions or small and easily monopolized. Technologies or transactions have to be used to make sure the company has a shot of owning a lot of the market and keeping the winnings. This concept naturally ties into having a margin of safety: a moat protects a company from others whereas a margin of safety protects a company from itself.

A useful example of using technologies and transactions to build powerful moats is Color Genomics. The company used vertical integration and relied on a Supreme Court ruling to a whole new DTC product in the BRCA screening market.

In life sciences, there are large markets everywhere. Disease is prevalent worldwide and healthcare everywhere needs a major transformation. In particular, drug development is one of the few industries where businesses are given a step-by-step guide (i.e. FDA clinical trials) to make billions of dollars. The key in life sciences is building businesses that can transform these markets but protect themselves from excess competition. Examples of moats are:

Partnerships to finance discovery and development work or minimize the need for a large salesforce

Access to cheaper supply

Owning the customer relationship

Technology enables new pricing structure

Economies of scale

Brand

Patents

High switching costs

Organization

Less dilution

Owners in any business are fanatical about dilution. This is particularly true in drug development. A company might end up worth $2B, but if it took $1B over the lifespan of the business that ROIC might not be worth it. It’s key for a great life sciences business to be financed uniquely.

What makes life sciences a little different than other industries, especially software is the capital intensity. However, many parts of life sciences are a unique place to build a new company because incumbents are willing to non-dilutively fund their future competitors. A great example of building a dilution-protective business is Adimab. The founders and team built a robust business focused on antibody licensing. They have a cash cow that helps the company from requiring more equity capital. This helps shareholders maintain their ownership and gives the business the ability to control its own destiny. All hallmarks of a great business.

Misunderstood business models

Great business models are pretty easy to define but hard to build. Earning the ability to get better terms or access new opportunities is very valuable but hard. Think Royalty Pharma’s ability to get attractive terms on debt than the next company. Or Illumina’s ability to prevent other sequencing companies from growing. Even Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway gets first look on many unique deals because of his reputation and underlying capital structure (i.e. float).

An example of a business model that was misunderstood at first is BridgeBio. The concept of financing early-stage drug development programs with debt was quite revolutionary in 2015 when BridgeBio was founded. By focusing on rare diseases, the company found a niche where its model can work out successfully.

Undervalued technology

An easy way to find great opportunities in life sciences is to find technologies that are relatively new or have been left for dead. Undervalued technologies are off-the-beaten track - maybe they are not in the right city or from the right university or the most fashionable technology.

Arvinas is a powerful example of this. PROTACs were a new invention in the early 2000s and faced some skepticism initially. However, the ability to selectively degrade targets and early data pushed Arvinas forward to take the technology into humans and build an incredibly valuable company. Early on, finding technologies that are hard to understand and value create unique opportunities to strike up partnerships where others cannot and raise capital on better terms (as long as the data plays out positively).

A winning franchise

For anyone in the field, being part of a business that has a strong organization and culture is extremely important. You want to be part of the Patriots or Packers franchises not the Bengals or Titans. A winning culture ultimately is the long-term moat that defines all great businesses.

Merck is an easy example to use. They have continued to improve patient lives worldwide for decades. Despite some mistakes along the way, the institutional memory within Merck has carried the business forward. In short, companies that have had large success in the past will probably keep on winning. People from these companies or lineages have much greater odds of success than others as well.

Monopolistic

Monopolies are very rare in life sciences; however, there are opportunities to own particular modalities, diseases, distribution channels, and more. Briefly, monopolies imbue almost magic features onto a business - a monopoly can experiment with its business model, invest heavily in R&D, and so on. Monopolies can also be very malignant, but that depends on the values of the founders and owners.

An example here is Regenxbio. They have a near monopoly over AAV gene therapies. Moreover, Regeneron had a major advantage for a while in fully human antibodies. Epic has one in EHRs. And as life sciences enters consumer markets more and more, the ability to create monopolistic businesses will become easier.

These eight drivers are analogous to many of the core lessons value investors hold dear across all industries. Ultimately, all great businesses serve their customers well from patients to scientists and clinicians and beyond. Thankfully, my freshman college roommate, Kevin Hirata, did me one of the best favors of my life by directing me to read The Intelligent Investor by Ben Graham. The book along with Graham’s other work focused on delineating investing from speculation. This help me understand that investing is best when it is business-like - investing confers ownership in a business and ownership ought to be valued: