Axial - BridgeBio

Surveying great inventors and businesses

BridgeBio is building an outsider moat in drug development. Instead of relying on a core technology, the company has a private equity firm specializing in drug development and clinical programs embedded in it. BridgeBio’s advantages are the scale they can offer an individual drug program and the discipline to know which ones are worthwhile to underwrite. If the business can maintain its independence (an extremely rare event in biopharma), then overtime, each iterative program will improve the odds of success for the next one. BridgeBio has the potential to become a Danaher or Constellation type of business model in drug development. The records of these companies suggest BridgeBio could raise the bar on the efficiency in the drug industry - increasing productivity and bringing treatments to more patients.

Key findings

A way to make drug development determinate is to focus on fields or classes of medicine that have had high amounts of research financed by other people and a rich history, and use this record to become a superforecaster (i.e. curation and management) in the clinic.

Using this approach, BridgeBio accrues values through clinical execution and like Walter Payton jumps over the pack to more reliably bring drugs to market.

New regulations in the 1980s enabled a new class of business model focused on rare disease that is slowly transitioning toward an outcomes-focused model.

BridgeBio has three major features that helps make its model unique: financing (i.e. from unique sources), portfolio (i.e. multiple shots on goal), and curation (i.e. discipline).

Models reliant on a small internal team and distributed development need a strong system and playbook to share across their network to maintain quality and discipline.

Technology

BridgeBio relies on human genetics for drug development. BridgeBio’s technology is premised on pursuing diseases with well-characterized genetic targets in order to improve the odds of success of their 16 program pipeline (image below). Instead of having a core engine and platform to drive success, the company relies on growing and managing a portfolio of drugs well. This type of portfolio approach is hard to pursue if a company doesn’t have a method to tilt the odds in their favor - for BridgeBio relying on human genetic targets and rare diseases allows the company to focus on clinical execution instead of R&D.

Source: BridgeBio S-1

This doesn’t mean BridgeBio has no technology, but instead of trying to make new breakthroughs, the company relies on the broader field of genetics to carry a lot of the freight and increasingly, BridgeBio can potentially create a unique data set and method to improve curation in drug development. In the field, most tools and in particular software has been focused on preclinical development. Over the next 5-10 years, we’ll see the success rate of models produced by companies like Recursion and Insitro. But for everything around clinical development, which one can argue is the most important part of making medicines due to the capital intensity, the tooling is pretty sparse.

To be successful, BridgeBio doesn’t need to get really good at predicting clinical trial success. Competition might force this, but BridgeBio’s portfolio approach and financing structure likely will be able to bring at least one drug to market. For the whole industry, this is incremental, but for the business and shareholders, it is incredible. But overtime, BridgeBio could build the suite of tools to improve clinical success thereby strengthening its technical moat of curation and management - that would be truly disruptive. BridgeBio has a better chance than most to accomplish it (image below of BridgeBio framework):

Source: BridgeBio S-1

Modeling clinical trials is nothing new, large biopharma are always trying to find an edge in the marketplace, but everyone in the field cannot get around the long feedback cycles in the field - 10 to 15 years. Software has a near instantaneous feedback cycle. A movie’s success can be measured over a weekend. A bridge’s viability can be modeled out and stressed tested in months. All of these fields have a rich record of history of success and failure - in short, they are determinate. Most fields in biology are indeterminate (i.e. relying on the odds and whims of nature). There are specific sub-fields that are becoming more predictable. Knowing these areas is an incredible advantage to identify and form unique businesses. Over the last few decades, mostly due to high levels of investment, human genetics has become more determinate especially relative to other things in biology and medicine. We’ve socialized the unproductive aspects of studying the human genome and this gives a rigorous business, like BridgeBio, the opportunity to jump over the pack, and create and capture a lot of value. By understanding genetics increasingly more and having the history of genotype/phenotype combinations, BridgeBio could subvert the traditionally long feedback cycles in drug development in a niche of rare disease indications (i.e. diseases that have patient populations below 200K).

Technically, a good way to describe BridgeBio is that of a superforecaster. Any business that wants to do this in drug development needs a framework and history addressing the following features:

The underlying biology - probably the most important part (i.e. MoA)

Pricing of the drug if approved

Competition in an indication

Safety especially during post-approval monitoring

Physician practices (i.e. prescription) and culture

Regulatory environment

This all assumes there is a demand for the drug. Any method for drug development usually starts out with understanding why patients need a drug. Without this, everything else is pretty useless. BridgeBio communicates their framework succinctly as reducing risk for discovery, development, regulation, and commercialization. If any class of disease will become forecasted, it’s probably going to be rare diseases due to the predictable market uptake and reimbursement along with competitive protection (i.e. market exclusivity).

To become a superforecaster in drug development, understanding the biology is really important. Unfortunately, most fields in biology are not as well understood as we would like, but this represents a large opportunity set for inventors to change human health and nature. Fortunately for patients, a lot of biopharma companies, and BridgeBio, many rare genetic diseases are pretty well-characterized. This has given rare disease drugs the ability to have around a 3x higher success ratethan other classes. This is a result of a combination of incentives (Orphan Drug Act, Breakthrough Designation - image below) and investment in genetics. For BridgeBio’s benefit, rare diseases have a higher ROI than other indications - on average ~2x due to how acute these diseases are. With the higher return and lower clinical and scientific risk, BridgeBio is in a rich niche when compared to the broader drug development field.

Source: Alexis Borisy

There are thousands of rare diseases with many having a characterized genetic cause (i.e. Tay-Sachs, sickle cell anemia). With an addressable patient population well over 300M people, BridgeBio has a large opportunity set to pursue. In combination with a lot of indications, genetics of rare disease helps improve success in drug development by:

Understanding the progression of the disease often through natural history studies (mapping out genotypes to phenotypes)

Having biomarkers to measure efficacy and stratify patient populations

Improving disease models that can identify drugs from approaches like target-based and phenotypic screens

The value of sequencing genes and whole genomes to understand the mechanism-of-action

Better-than-average drug response predictive power

However, clinical trial recruitment is incredibly difficult for rare diseases. Foundations do incredible work to help. Hopefully, companies like RDMD improve this process. However, improvements in pharmacogenomics ought to make N-of-1 trials possible (another topic to cover and hopefully a pioneering company emerges).

Moreover, some rare diseases are heterogeneous (i.e. Niemann–Pick disease type C) having many different genetic subtypes resulting in the same phenotype. This is an important technical bottleneck in field; BridgeBio is not trying to solve it - they are picking games where the genetics and pathology are well-characterized. But this touches upon a much larger problem in human genetics - genes that are well known are not necessarily more important for disease. Most well-characterized genes are so due to the tooling available early on or just due to chance. For BridgeBio, this is a wave to ride - let others characterize the genome and clinically execute when the time is right.

An approved drug is historically viewed as a rare event, but companies should strive to make successful drugs an expectation. Ultimately, if BridgeBio continues to execute well, they have the potential to become a superforecaster in rare disease drug development.

Market

BridgeBio is focused on genetic disease with most having patient populations below 200K. The key driver of success for this overall market is the increased clinical success rate of rare disease drugsversus high prevalence disease drugs (25.3% versus 8.7%). This is due to a variety of reasons:

Rare diseases often have faster and smaller trials

Likely have lower target risk

FDA spends more time helping rare disease drug companies driven by advocacy groups and incentives

Despite the small patient sizes of any given disease, the increased ability to bring a drug to market combined with the current ability to charge high prices per patient, rare genetic diseases are in aggregate a large opportunity with high demand.

Briefly, predominant business models in drug development have roughly followed this track over the last 5 decades or so:

Blockbuster (1940s-1990s) - selling a drug at a cheap price for many people

Rare disease (1980s - 2020s?) - selling a drug at a high price for a few people

Full stack - driven by the shift to fee-for-value; focused on outcomes not prices

It’s hard to say when the rare disease model will take a backseat to the full stack model, but there is a carrying capacity of drug prices society can bear. We haven’t reached it though. BridgeBio and other companies will have to overtime focus on outcomes as the overall incentives in healthcare change.

On incentives, The rare disease model became viable after the passing of the Orphan Drug Act (ODA) in 1983. In the US, this gave drug companies the incentive to develop treatments for rare diseases providing:

A tax credit for 50% of clinical trial costs

Sever years market exclusivity

Research grants

The new law worked: before the ODA, only ten drugs for rare diseases were approved by the FDA. Afterwards, more than 300 rare disease drugs have been approved with now over 1/3 of all FDA-approved drugs focused on rare diseases. BioMarin is a case study of success for rare disease; significant value was created when they began to focus on certain classes of rare disease around the mid-2000s.

Combined with the ODA and our improving understanding of human genetics, the market for BridgeBio represents $10Bs of value. The overall size is important but for a given business, the specific indications matter more. The market opportunity for BridgeBio is compelling because of the size, predictivity, and need.

Business model

The business model is the most interesting part of BridgeBio. Instead of being a single-asset play, BridgeBio aggregates many different programs, now at 16 with 4 in late-stage development), to increase the odds of clinical success. This type of rollup model can be dangerous if financed irresponsibly (i.e. Valeant), but can work well particularly for genetic disorders due to the large number of assets sitting on the shelf from a decade or so of genomic discovery. BridgeBio has three major features that helps make its model unique: financing, portfolio, and curation.

Financing

The financing model of BridgeBio is based on the work of Andrew Lo from MIT(an investor in the company). His work has led the way on researching new models to finance drug development. Lo has discovered a pathway to generate meaningful returns by financing drug development with a much larger pool of capital, using both equity and debt, than that of a typical venture capital fund:

Source: BridgeBio, Andrew Lo

In the model, many (ideally non-correlated) projects are conducted in parallel rather than serially. With enough capital, this approach reduces risk found in drug development and improves the predictability of financial returns. The model already works in other industries like films and mortgages. History and feedback cycles makes the model difficult in drug development, but BridgeBio has found a successful niche in rare genetic diseases.

Excitingly, BridgeBio has attracted general sources of capital that wouldn’t necessarily be interested in drug development. Overall the company has raised over $700M with the recent IPO raising around $300M:

Source: BridgeBio

This type of model has recently proliferated likely due to cheap financing options. In the past, the portfolio model proposed by Lo was not possible due to the large capital requirements and limited opportunities. But this has changed recently especially in specific disease and drug classes. Other examples in drug development are Blackstone Life Sciences (aka Clarus), Roivant, UBS Oncology Impact Fund, and ElevateBio, and even outside of biopharma, in synthetic biology like Visolis and diagnostics like Danaher. Outsider moats can seem attractive initially due to leverage but can easily become a roll up that will blow up eventually if management and shareholders are not willing to pass on deals and are optimizing for short-term growth. Time will show which companies are disciplined and which are not. So far BridgeBio has demonstrated good judgement in what programs to pursue. In the long-run, one of BridgeBio’s major advantages is discipline and not letting the financing have an effect on scientific plans. The business model is less about technology and more about personnel - something harder to predict for most people. Having the patience to deploy the large amounts of capital in the backdrop of easy financing is a competitive advantage. Lo has discovered that over $5B of capital needs to be deployed in this model to generate returns over 10%. With around $700M in capital, BridgeBio is in the early-stages of its execution and as its drugs become late-stage clinical assets, the company will need to tap debt markets to succeed. This is part of general shift toward financing drug development with debt as it becomes more predictable. Overtime, there will be a pathway to conduct LBOs on drug companies and life sciences businesses in general.

Portfolio

BridgeBio’s model also relies on having a portfolio of rare disease drug candidates that are more likely to get to market that other drugs:

Source: BridgeBio, BIO

For BridgeBio, rare genetic disease is low-hanging fruit given progress in multiple fields over the last decade (i.e. clinical genetics, patho-physiology). By relying on genetics, the company can start with a hypothesis with a better chance of success than average across the spectrum from pre-clinical to late-stage development. Often BridgeBio knows the exact cause-effect relationship in disease. By underwriting many programs at the same time, BridgeBio reduces risk of clinical failure. An overlooked aspect of BridgeBio’s portfolio model is the lower barriers of entry to commercialize drugs for rare patient populations. This is due to regulations and the fact that rare disease communities stick together. The latter will only become a more powerful force for BridgeBio as companies like RDMD build valuable networks for rare disease drug developers to plug into.

From Andrew Lo’s research, the portfolio approach relies on 4 main inputs:

Correlation of clinical outcomes for each asset

Price

Probability of approval

Stage of assets

From this work, Lo models that the portfolio model will only generate enough return on the large amounts of capital for the private-sector as long as drugs are priced above $500K-$1M. Foundations and the government can relieve this financial risk through grants and guarantees. Overtime, and Lo agrees with this, new pricing models (i.e. outcomes-based) need to be considered that could change the potential rewards for companies like BridgeBio.

Curation

BridgeBio’s decision-making is supported by a core team in Palo Alto of around 50 people. Large drug companies could do what BridgeBio is doing, and some will, but many will not succeed due to a lack of curation despite having the capital and pipeline. As a result, most drug companies would be wise to execute a bank-like business model (i.e. AbbVie buying Allergan, BMS buying Celgene) - using their balance sheets to underwrite lower risk projects (i.e. approved drugs). This can help the broader ecosystem by providing large exits for successful companies and programs. Unlike other companies, BridgeBio focuses on genetics diseases where it has specific expertise. The idea is to become increasingly more efficient in picking which drug programs to pick up. The long-term goal set out by the company is to become as large as peers such as BioMarin bringing drugs to market themselves (i.e. buy-and-hold not buy-and-sell). However, with a relatively small internal team, BridgeBio gains scale through spin-outs and partnerships.

As a result, companies like BridgeBio need a strong system and playbook to share across their network to maintain quality and discipline. The best example is Danaher Business System (DBS). Just as Danaher took kaizen and applied it to industrials and diagnostics. New companies should just take DBS and apply to every other industry especially drug development. The curation part of BridgeBio has a few parts:

General R&D capabilities to gain scale (technology agnostic)

For a specific disease, have a separate entity to bring on board experts

Each organization has their own equity to incentivize these experts

In this process, BridgeBio figures out which programs have high enough expected returns. Over time this curation engine needs to get better. Currently, the company has pursued diseases such as amyloidosis, canavan disease, molybdenum cofactor deficiency, Netherton's syndrome, mitochondrial disease, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, epidermolysis bullosa, pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration, Darier disease, and emphigus; across many types of targets including transthyretin, v-raf-1, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1/2/3, kallikrein 7 (chymotryptic, stratum corneum), kallikrein related peptidase 5/14, KRAS, tyrosine phosphatase, sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase 1. An analysis of this pipeline shows a NPV high enough to justify further investment into the business. Showing an ability to more selectively choose which indications and targets to go after will convey BridgeBio’s ability to become a very large company.

The most important tool for successful curation is forecasting. For BridgeBio and almost every life sciences company the goal is trying to predict phenotype from biological information. An interesting example to call upon is Monsanto; the company was a pioneer in using molecular biology to engineer seeds. The company developed a set of tools to make plant trait development less uncertain and became one of the few life sciences companies benefiting from network effects (i.e. pooling together yield information from each individual grower to design better seeds); one caveat is that they had to deal with much less regulation working in agriculture. However, the lesson is valuable to understand where BridgeBio can grow. Other companies like 23andMe are also using phenotype/genotype data to improve drug development. Overall, if drug development can become as accurate as forecasting crop yields, these medicines can be versioned and solve the problem of decreasing productivity in the field (image below). However, I would say the Eroom curve is not totally correct because it is not normalized for cures and lifespan extended:

Source: Nature

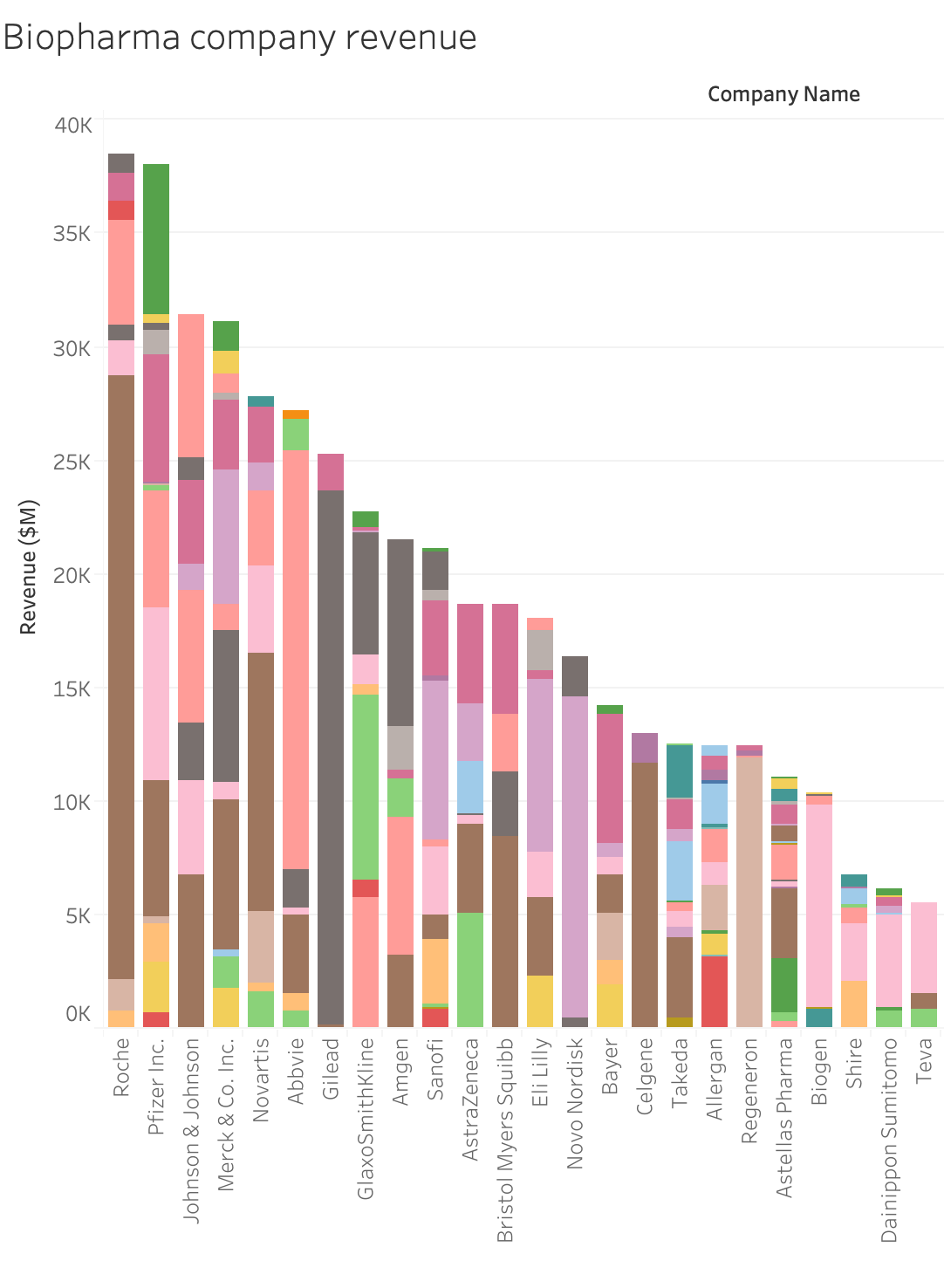

Similar to a lot of other blockbuster industries (i.e. Hollywood, venture capital), drug development is power law driven. However, this phenomenon is more pronounced for products instead of at the company level (image below). This succeed in this type of environment, BridgeBio is executing unique transactions in parallel:

BridgeBio & Cincinnati Children’s Hospital (11/2018) - research project for genetic diseases.

BridgeBio/PellePharm & LEO Pharma (11/2018)- equity, license, and option deal for patidegib in Gorlin syndrome and an option to acquire PellePharm.

BridgeBio & St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (6/2018) - licensing of small molecule therapeutics for pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration.

BridgeBio & CoA Therapeutics (6/2018) - licensing and spinning out of CoA Therapeutics to develop small molecules for rare genetic disorders.

BridgeBio & Fortify Therapeutics (6/2018) - licensing and spinning out of Fortify Therapeutics to develop NVP015 for Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy.

BridgeBio & NeuroVive Pharmaceutical (6/2018) - licensing NVP015 succinate prodrug chemistry program for genetic mitochondrial disorders.

BridgeBio & Origin Biosciences (6/2018) - licensing and spinning out of Origin Biosciences to develop ALXN1101 for molybdenum cofactor deficiency Type A.

BridgeBio & Alexion (6/2018) - asset purchase of cyclic pyranopterin monophosphate replacement therapy (ALXN1101).

BridgeBio & Novartis (1/2018) - licensing of infigratinib (BGJ398) FGFR kinase inhibitor to be developed by QED Therapeutics.

BridgeBio & Eidos Therapeutics (4/2017) - licensing and spinning out of Eidos Therapeutics to develop AG10 small molecule treatment for transthyretin amyloidosis.

Source: BridgeBio S-1

Right now, Humira is the top-selling drug in the world: