Axial - Adimab

Surveying great inventors and businesses

Adimab showed a licensing model is a pathway to build a large business in the drug industry. Founded in 2007 by Dartmouth professor Tillman Gerngross who had previously sold his last company, Glycofi to Merck, Adimab created a platform that solved the intellectual property conflicts in antibody discovery that existed at the time. Large biopharma companies were able to get access to high-quality antibodies without potentially infringing on other company’s claims. With a polarizing position to use yeast instead of mammalian systems, Adimab had a more scalable technology to build a long-list of partners. This decision helped Adimab get the head-start it needed to break away from the pack like companies Abgenix and AnaptysBio. Ultimately, Adimab is the canonical example of how to build a unique business model in drug development.

Key findings

The major problem Adimab solved was legal not technical - it created a platform that served as a one-stop shop for antibodies in an environment where larger companies had difficulty building out their own processes due to the potential of infringement.

Adimab’s model was not an overnight success - the amount of technical and business development work and patience over the last 10 years required put Adimab in a flexible position to remain competitive over the next 10 years. Many of Adimab’s contemporaries were not able to enjoy similar success.

Technology

The core technology for Adimab, Antibody Discovery Maturation Biomanufacturing, is centered around using yeast to engineer and manufacture antibodies. The company engineers yeast to do what a B-cell does. Their yeast display system monitors antibody/antigen interactions sorting the yeast cells that light up through a fluorophore. Secretion is induced in the sorted yeast cells and the functional antibodies are collected. Often times these antibodies are optimized in mammalian systems if the right pattern of post-translational modifications cannot be added in the yeast system. As opposed to phage-displayed libraries, which screen fragments of antibodies for binding and need to reassemble the entire antibodies and hybridomas, which does not scale and is expensive, Adimab’s method was able to discover human antibodies (image below) at scale. At the time, this gave the company an incredible technical advantage - the company could deliver at least 100 functional antibodies in 8 weeks making it hard for other companies to come close (at the time, most companies would offer a handful of antibodies per target in a few months). This helped give the company the head-start to execute its business development strategy thereby enabling Adimab to have the most functional and diverse libraries of human antibodies at the time.

Source: Adimab

At the time, the major problem Adimab solved was legal not technical. No one biopharma company had access to the suite of patents to build a full platform in antibody discovery. In order to create a one-stop shop for antibodies, Adimab did a tremendous amount of work to analyze the hundreds of different patents in the field and design a platform that wouldn’t infringe on most of them. Consequently, their first business deal was the purchase of a patent portfolio. By deliberately creating a platform that minimized royalties to other companies, Adimab was in the position to scale up quickly and solve the legal problems large biopharma companies were facing.

Yeast display

The core technical engine for Adimab is using yeast to display antibodies to monitor their binding against targets. Major advantages of this method as compared to traditional methods at the time:

Eliminate binding artifacts due to the bias found in the host expression system

Enabled multiple readouts in parallel to measure binding affinity and expression to have more predictive power of antibody stability and affinity

Via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), allow quantitative screening of antibody screening

However, yeast display can have a smaller library size (~10^9) versus phage display (~10^11). But at the time, too much focus was on finding antibodies solely based on affinity. Despite the lower library size, Adimab used its technical advantages to run discovery programs that optimized for drug-like properties in general like binding affinity, epitope coverage, expression, solubility, stability, and other features that would improve the odds of clinical success. One of the co-founders of Adimab published a framework to assess various features of antibodies to assess their potential success rates - described below.

On top of the yeast display platform, Adimab then added new parts to strengthen their moat. Early on the company added optimization to antibody discovery and over time implemented mammalian production, bi-specific discovery, common light-chain libraries to reduce heavy-chain/light-chain mispairing, and B-cell cloning. At its founding, Adimab was meeting high clinical demand and studies at the time showed biologics had a ~2x higher success rate in clinical development. To ensure their plan worked, the company focused on human IgG antibodies that circulate in the body for weeks improving dosing and efficacy. As new targets emerge, new formats of antibodies (image below) will likely benefit from models similar to Adimab. It’s no wonder Adimab is pointing its cannon toward bispecifics now as the modality is seeing more success:

Source: Absolute Antibody

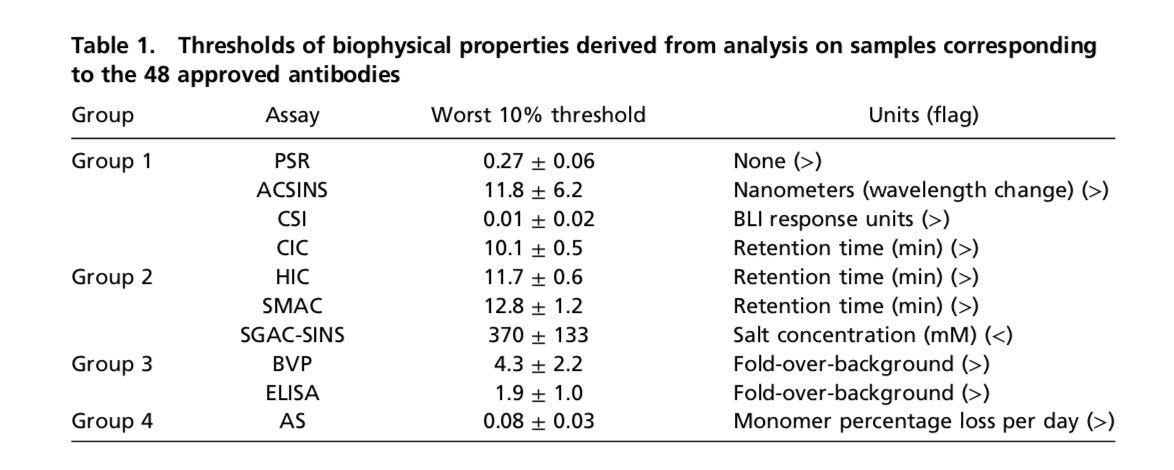

In 2017, Dane Wittrup (co-founder) led research to study 137 clinical-stage antibodiesand 48 approved ones and understand what makes them successful. Similar to how small molecules have Lipinski’s Rule of Five as a framework for design, the research sought to do something similar. This is another important theme for drug companies - can engineering principles and software be used to create Lipinski’s Rule of Five for other modalities like natural productsand CARs.

Wittrup’s group measured 12 features of their antibody set (image below) for things like hydrophobicity, specificity, stability, and expression. From the analysis, the team discovered that no one assay predicted failure and instead used a weighted model. Across the 12 measurements, red flags were given to an antibody if it was in the bottom 10% of the range. More than half of approved antibodies had no red flags while earlier-stage molecules had a much higher frequency. This research is indicative of the frameworks Adimab and other drug companies need to build out in order to make their discoveries more successful:

Source: PNAS

Source: PNAS

Business model

The first deal Adimab executed was the purchase of a yeast-based antibody discovery patent portfolio from Genetastixin the summer of 2007 (mainly to add glycosylation technology to their yeast platform). It’s earlier deals were incredibly important to validate the platform - ATUM (9/2007), Merck(6/2009), Roche, with Merck was one of the bigger breaks (6/2009), Merrimack Pharmaceuticals (11/2009), and Pfizer (12/2009). One aspect of the business model not widely appreciated retrospectively, was how long it actually took for the model to scale up - Adimab by one means was an overnight success. Now the company partners with some of the best drug companies in the world (image below), issues a private dividend having paid backed the investment principal, and designed one of the most important business models in the field.

Founders

At the formation of the company, Gerngross was joined by one of his students, Errik Anderson, to scour through the antibody discovery patent literature. Over time, they discovered that Dane Wittrup had done most of the great work in yeast display. This founding environment was a strong basis for the long-term decision making of the company - Gerngross had a prior exit and along with Wittrup, both of them had strong reputations for scientific integrity. The licensing model for drug development takes a very long time to generate meaningful returns if competition doesn’t take it first. This is a major reason why internal drug development is a chosen path for most companies - owning the asset and having a clear regulatory pathway to follow is often a more attractive opportunity. This long-term approach helped Adimab get the scale of partnerships that has generated some level of lock-in most biopharma services do not have.

Lock-in and moats

Due to its track-record now, Adimab can command better deals. Its original competitors have either been acquired, closed down, or shifted their approach and the new ones don’t have the history just yet. As a result, Adimab’s recent deals can generate significant upfront/milestone payments and royalties with relatively long commitments - 5-7 years often. The duration of these deals creates a moat around their discovery platform and services.

Source: Adimab

Beyond lock-in which over a 5-year cycle can slowly deteriorate, Adimab will need to continue to update its platform as it has already done. Some licensing models can transition to internal development overtime in order to accrue more value; however, Adimab has communicated a purpose to focus on services for biopharma.

For Adimab continuing to monetize its discovery platform while fending off a new generation of antibody companies is the next challenge. An original thesis of Adimab was to never compromise its platform, unlike other drug companies historically, by avoiding the clinic. As new formats of antibodies come to market, Adimab has been using this platform to gain a competitive edge for new use cases. An important feature of Adimab’s deals have been non-exclusivity for targets allowing the company to work with multiple companies that are experts in their targets and indications. By focusing solely on discovery and scaling up partnerships, Adimab ended up very capital efficient with enough cash-flow to be returned to shareholders and reinvested into the company. This has given the business an incredible amount of flexibility to make a strategic transition and not compromise its mission.