Drugs that are their own pipelines

Life sciences strategy

Axial partners with great founders and inventors. We invest in early-stage life sciences companies often when they are no more than an idea. We are fanatical about helping the rare inventor who is compelled to build their own enduring business. If you or someone you know has a great idea or company in life sciences, Axial would be excited to get to know you and possibly invest in your vision and company . We are excited to be in business with you - email us at info@axialvc.com

Drugs that are their own pipelines

Pipeline-in-a-pill is a drug development strategy where one drug is used for multiple indications. Some of the world’s best-selling medicines ever from Humira to Keytruda are drugs that are their own pipelines. Other strategies in the field are building a portfolio or using a platform; however, studying what features make drugs have the ability to be a pipeline themselves is valuable because it is the hardest strategy to pull off and the most impactful. The strategy also creates a very efficient drug development business: it becomes more about clinical execution than finding the next blockbuster.

A company can gain broad therapeutic and commercial potential from a single drug using the pipeline-in-a-pill (PiP) strategy. It’s an offensive strategy where a company takes a concentrated risk, hopefully informed by the underlying mechanism and data, to maximize the upside of an asset. When it works, PiP can create large outcomes. This is also shown by recent M&A activity for medicines with PiP potential: Bristol Myers Squibb’s acquisition of Myokardia in 2020 for $13.1B for its cardiovascular drug, mavacamten, Gilead acquiring Forty Seven the same year for $4.9B to gain access to magrolimab, an anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody, and Johnson & Johnson’s acquisition of Momenta Pharmaceuticals in 2020 for $6.5B for the company’s anti-FcRn antibody, nipocalimab. Why are these PiP drugs so valuable?:

Lower clinical costs - once a drug is approved in one indication, the initial costs of the first trial can be amortized across the new trials initiated. A company does not have to start new discovery and preclinical projects since it already has a golden goose it can test in more indications.

Maximize commercial potential - the drug can pursue multiple, discrete patient populations that maximize its addressable market size

Commercialization efficiencies - with only one drug, a company can realize substantial sales and marketing savings, and each new approval and its market uptake is often amplified by the previous approval(s)

On the other hand, the PiP strategy is vulnerable to new entrants, in particular fast followers. Moreover, a company has a lot riding on one candidate, and if the drug fails its first trial, the entire program’s value could go to zero pretty quickly. Soliris is an exception on this part. And Incyte’s failure with epacadostat, an IDO inhibitor, for solid tumors is a confirmation of this concentration risk.

This analysis focuses on a few case studies of drugs that became their own pipeline: Soliris, Keytruda, Humira, Avastin, Rituxan, Avacopan, Advair, Neupogen, and Revlimid. These transformational medicines became a pipeline-in-a-pill for a few of these reasons:

A broad mechanism-of-action (MoA) often pursuing a target that is involved in multiple pathways and diseases. This is probably the most important feature to successfully execute a PiP strategy. Also, a broad MoA creates combination potential that only enhances the value of the drug.

Differential dosing and delivery to have the ability for a drug to treat patients in different settings. An example is the use of Methotrexate in oncology (at high doses) and lupus/rheumatoid arthritis (at low doses).

A target that is genetically defined to de-risk the clinical program. This is the preference for all drug developers though.

Long-term safety studies and more efficient trial design to get to new pivotal studies sooner.

The pipeline-in-a-pill strategy is a viable one for new drug development companies to take. The prevailing approach is using a platform, which has its own advantages; however, PiP used by itself or in combination with other strategies, can create a more scalable business. For drug candidates, product-disease fit is the most important aspect to consider. Is the MoA driving the disease pathology? Are the right biomarkers and endpoints being used for the product? Whereas for platform companies, the most important consideration is platform-partner fit. Is there demand from large companies for the platform and technology? Can the platform create disease-focused deals? Millennium is the canonical platform company here. Ultimately, developing drugs that are their own pipelines is fraught with many risks and challenges, but their impact on human health and medicine is so transformational that more companies ought to consider the strategy.

Key findings

These 9 examples of drugs that are their own pipelines highlight the enormous patient impact and business scale that the PiP strategy can achieve. Other drugs that have had similar success like Imbruvica and Opdivo are worth mentioning. Companies such as Seattle Genetics, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Aravive, and Kezar Life Sciences are in positions to build similar franchises. There are also opportunities to bring the PiP strategy to other indications like neurodegeneration, aging and age-related disease, and respiratory disease.

Complementary strategies to pipeline-in-a-pill are building a portfolio of assets or a platform. The former focuses on using a diverse product portfolio as the moat and the latter focuses on technology as the moat. The pipeline-in-the-pill strategy has the actual drug (and its clinical success) as the moat. If PiP is offensive, the portfolio strategy is defense. In a given indication, a suite of drugs across different disease stages can help a company keep sales steady despite new entrants.

For founders and inventors, these strategies create 3 main paths: (1) develop an asset with pipeline-in-a-pill potential, (2), build a company to be bought and integrated into a larger portfolio, and (3) use a platform to execute partnerships and make new medicines. The rare company could figure out a way to do all three.

Soliris

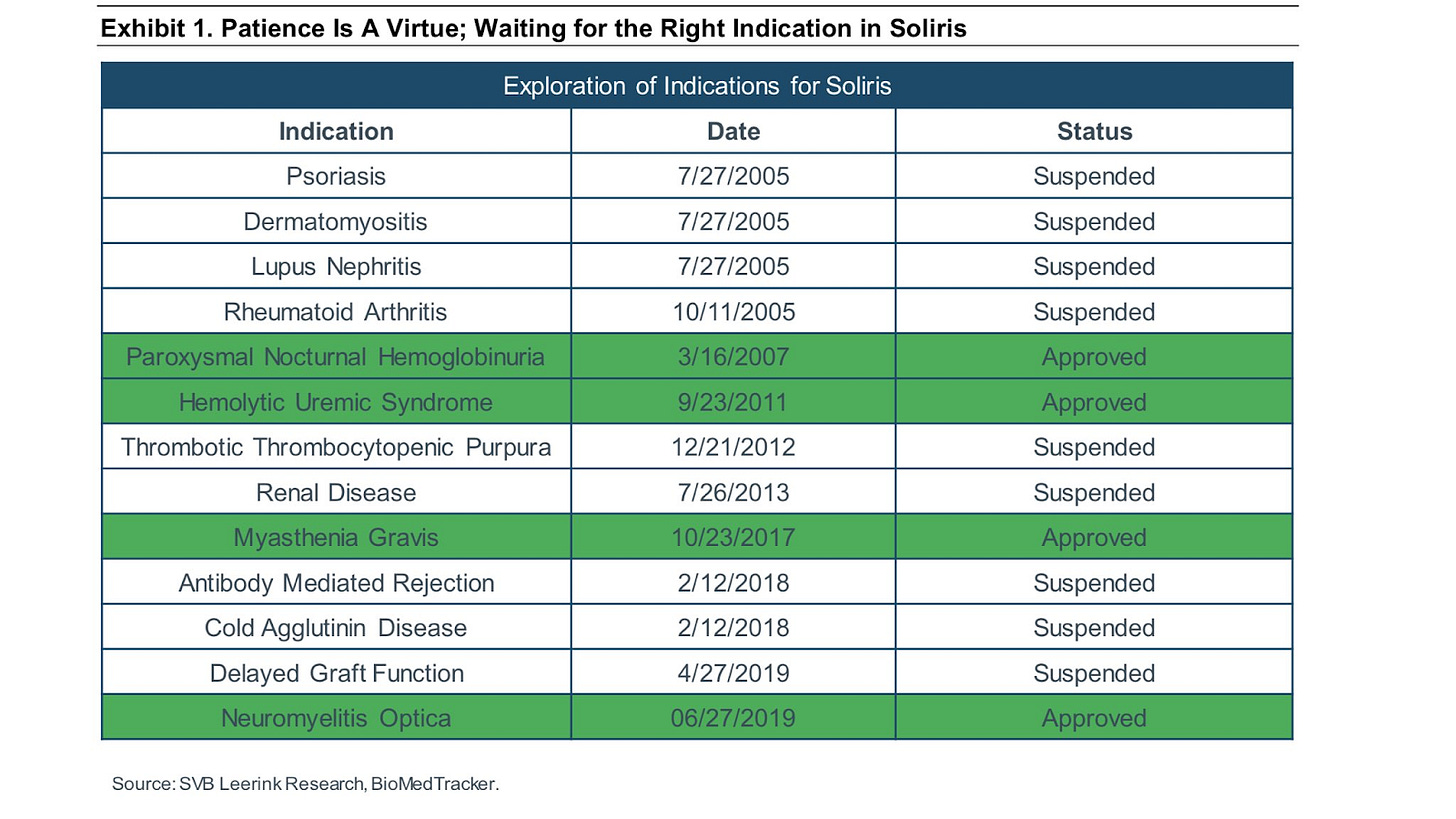

Soliris (eculizumab) is an antibody complement inhibitor that has transformed the lives of patients with ultra-orphan diseases and built up Alexion as an iconic drug development company. Soliris is an example of a drug that is its own pipeline: with 4 large-scale successes over the last ~2 decades along with 9 failures.

In 2007, Soliris was approved to treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) after 4 suspended trials. In 2011, the FDA approved Soliris to treat atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). The drug was the first approved medicine for either of these ultra-rare orphan diseases. Overtime, Soliris received approval to treat adult patients with generalized myasthenia gravis (MG) and neuromyelitis optica (NMO). Alexion has pursued a portfolio strategy on top of its pipeline-in-a-pill strategy - develop other complement inhibitors while still working on expanding the use of Soliris across more indications. What has enabled Soliris to become a drug that is its own pipeline is the focus on complement, which drives the pathology for many immunological diseases.

The founders of Alexion were not only pioneers in validating the ultra-rare orphan disease business model but set a great example of how to position one drug as its own pipeline. The company had failures in larger indications like RA and lupus. By focusing on ultra-rare diseases that have low-quality or no standard-of-care and can have more efficient clinical trials supported by the FDA, enabled Alexion to build a franchise. Soliris is a very useful case study of how one drug can treat more than one condition expanding its label over time.

Keytruda

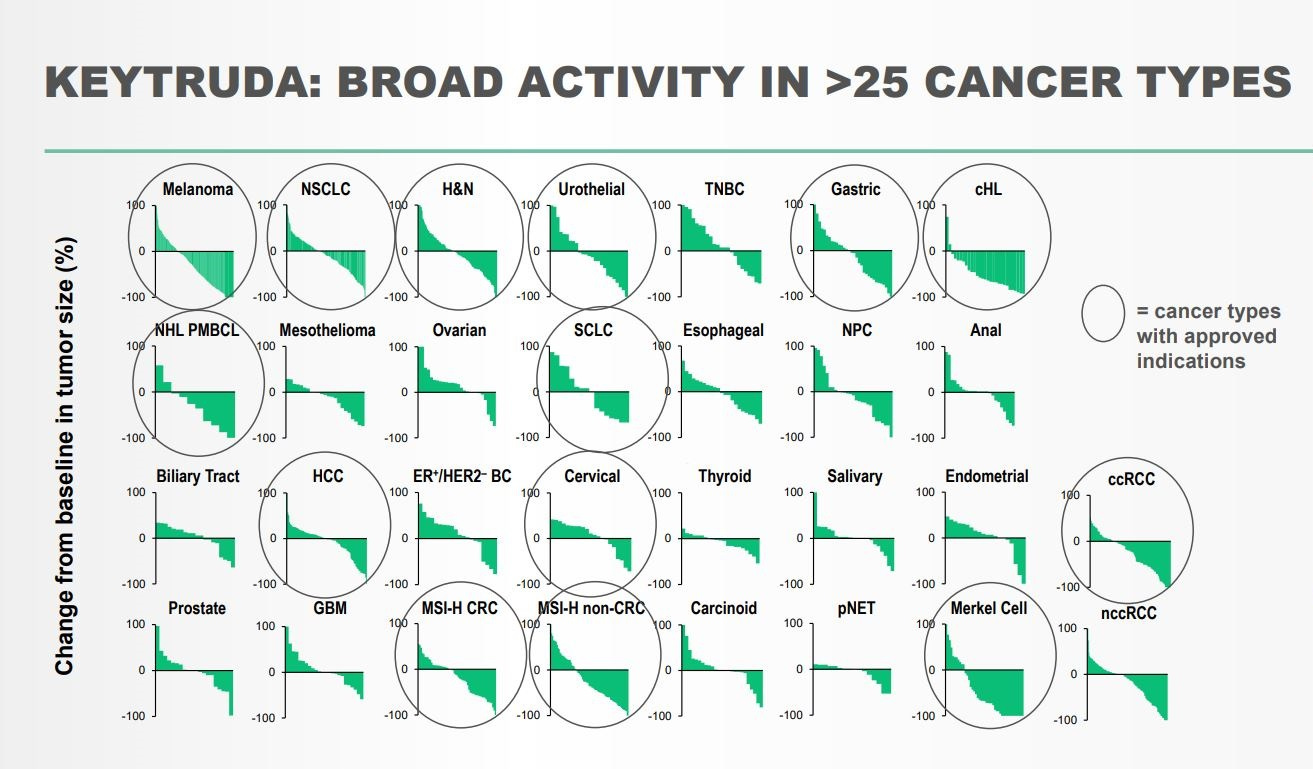

Keytruda (pembrolizumab), an anti-PD-1 antibody, is one of the most transformative medicines ever. Approved in 26 different diseases, the medicine is one of the best case studies of a pipeline-in-a-pill strategy. The drug was initially developed by Organon during an 2003 effort to find PD-1 agonists to treat autoimmunity. With the company discovering an PD-1 antagonist, they decided to pivot to cancer with the attention given to CTLA-4 inhibitors at the time. They developed a humanized version of the antibody and began planning clinical trials. But in 2007, Organon was acquired by Schering-Plough, which was acquired by Merck in 2009. After two handoffs, pembrolizumab was put on an out-license list by Merck. In 2010, Bristol Myers Squibb reported positive phase 3 data in the NEJM for an CTLA-4 inhibitor, Yervoy, in refractory metastatic melanoma. With this news along with rumors that Bristol’s Opdivo, which targets PD-1 as well, was showing promising results, Merck decided not to sell over pembrolizumab and began the first clinical trial in 2011.

Some of the key decisions during this time that has led to Keytruda’s massive success was due to the realization that Merck was about 5 years behind BMS in the development of an PD-1 inhibitor:

Use of biomarkers - Merck used PD-L1 expression in tumors as a way to improve the odds of success for pembro. Even though biomarkers reduce the total number of addressable patients and make prescriptions a little harder, Merck chose to go down this route as a way to make up for lost development time.

Breakthrough designation - in 2012, the FDA implemented breakthrough designations, which increased the frequency of meetings with the agency and company. Merck took advantage of this regulatory change and got this designation for pembro.

Phase 1 expansion - when melanoma patients were observed to respond well to pembro, the phase 1 trial was expanded to add more advanced melanoma and lung cancer patients. The trial ended up recruiting over 1000 patients and became the largest phase 1 trial in cancer ever.

Focus on melanoma - pembro’s initial development in melanoma was driven by Yervoy’s initial success in the indication and their focus on advanced melanoma patients was not only made based on data but Merck’s desire to avoid comparator studies that could slow down clinical trials

In 2014, Keytruda was approved by the FDA to treat patients with advanced melanoma with a BRAF mutation. In 2015, the medicine was approved for PD-L1-expressing metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In 2016, Keytruda gained approval in recurrent.metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and as a first-line treatment for metastatic NSCLC. In 2017, driven by the discovery that microsatellite instability (MSI) is a marker for Keytruda responses, the medicine was approved in 5 different indications including the first approval based on a common biomarker, MSI. The drug picked up 6 more approvals in 2018 and has continued its impact on more-and-more cancers patients.

Humira

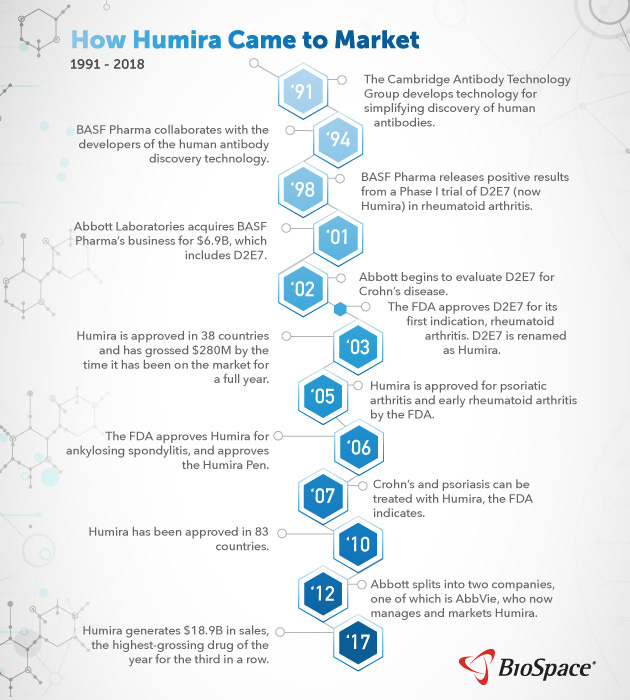

Humira (adalimumab) is the best selling drug ever with well over $100B in cumulative sales treating over a million patients. The drug, which stands for Human Monoclonal Antibody In Rheumatoid Arthritis, is an anti-TNF monoclonal antibody that treats several autoimmune diseases from rheumatoid arthritis to Crohn's disease and psoriasis.

In the UK, Cambridge Antibody Technology (CAT) Group used their phage display technology in the 1990s to discover what would become Humira. CAT was founded by Greg Winter who recently won the Nobel Prize for the invention of phage display. Around 1993, CAT raised capital from Knoll Pharmaceuticals (BASF) who pushed CAT to develop an anti-TNF antibody. Within two years a drug candidate was discovered. In 1998, BASF reported positive phase 1 data (n=140) for the drug candidate to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA). After positive phase 2 data, a pivotal phase 3 trial was initiated in 2000. With this exciting clinical traction, Abbott Laboratories acquired BASF Pharma for $6.9B in 2000. Humira was approved by the FDA in 2002 for RA. By the end of 2003, the drug had been used in over 50K patients. Despite being the 3rd TNF-α-targeting antibody on the market, Humira had a better dosing schedule (weekly versus daily) and better tolerability, which drove quick market uptake. These advantages only grew with a 2006 approval for a self-injectable syringe to deliver Humira.

With this approval and a broad mechanism-of-action, Abbott saw the value of using Humira for more diseases: Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and juvenile RA. Driven by each new approval, revenue went up quickly reaching $1B in annual sales and going over $6B by 2010. In 2013, Abbott Laboratories spun off their drug business into AbbVie. Humira now represents over half of the company’s sales.

Core US patents for Humira expired in 2016, but the drug is still a bestseller due to the barriers to entry for the development of generic biologics (biosimilars) and periphery patents that extend into 2030. Humira has been able to become a pipeline-in-a-pill for several reasons:

Pursuing a target, TNF, that has a wide effect on several autoimmune conditions

Having a better dosing schedule versus competition

Easier delivery with the Humira Pen to enable patient self-injection

Investing in long-term clinical trials (eight-year studies) to comprehensively measure toxicity and other side effects. Particularly for TNF inhibitors, side effects are a major consideration, and this type of data package is an important advantage for Humira even with expiring patents.

These 4 factors have created a brand for Humira versus biosimilars and other TNF inhibitors like Remicade and Enbrel, which still lasts to this day.

Avastin

Avastin (bevacizumab) is an anti-VEGF-A antibody developed by Genentech and approved for a wide-range of solid tumors as well as used off-label to treat wet AMD. In 2004, Avastin’s first FDA approval was in metastatic colorectal cancer. The drug gained approval for advanced lung cancer in 2006 and for kidney cancer and glioblastoma in 2009. In 2014, Avastin was approved in metastatic cervical cancer and gained another five approvals from there. The drug was part of some controversy with its 2008 approval for advanced HER2-negative breast cancer and subsequent market pullout in 2011 after more clinical data was observed to show Avastin did not have a significant effect over the standard-of-care.

In 1989 during a research project in cardiovascular disease, Napoleone Ferrara and his group at Genentech were the first to clone vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is essential for angiogenesis (i.e. new blood vessel growth). The idea the group started exploring, enabled by Genentech’s science-first culture, was the anti-cancer effects of inhibiting angiogenesis. Past studies found a connection between blood vessel development and tumor growth. An important theme here was that the Genentech group was bringing new technologies (cloning and antibodies) to an old problem (angiogenesis). In 1993, the group discovered an antibody that inhibited VEGF and led to reduced tumor growth in a mouse model. Once a humanized version of the antibody was developed, what would become Avastin entered clinical trials.

With such a broad mechanism-of-action (MoA), Genentech initiated trials for Avastin across a wide-range of cancers. The drug failed to meet its primary endpoint in 2002 for a phase 3 3rd-line breast cancer trial. A pivotal phase 3 trial (n=925) in metastatic colorectal cancer showed Avastin increased progression-free survival by 5 months over the standard-of-care. The drug gained approval for the disease in 2004, 15 years after the first cloning of VEGF. Genentech continued to explore the application of inhibiting angiogenesis for more cancers leading to several more approvals for Avastin over the following decade.

Avastin became a pipeline-in-a-pill for two main reasons:

Relying on a broad MoA mediated through VEGF that is connected to several solid tumors and even eye disease. Having a first mover advantage definitely helped Genentech as well.

Bringing new technologies to explore an old problem: the role blood vessel formation in cancer growth

Rituxan

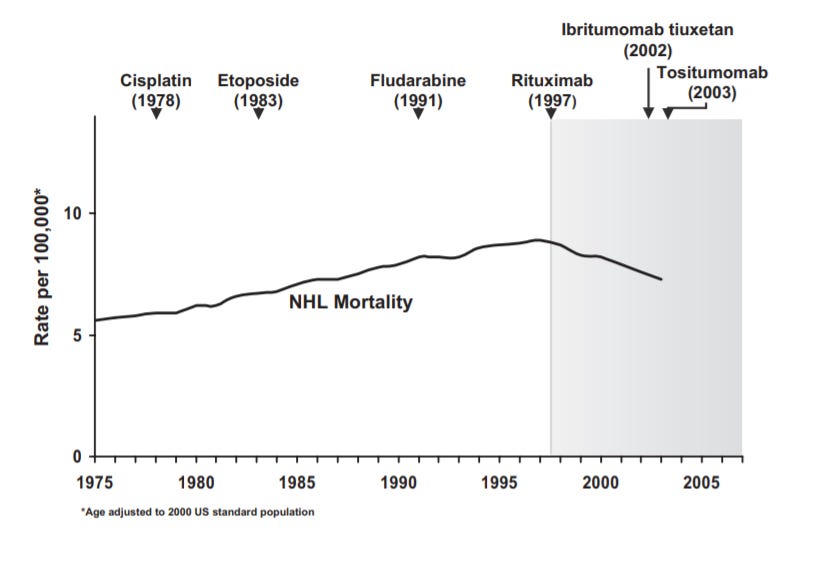

Another case study for the pipeline-in-a-pill strategy is also from Genentech through a collaboration with IDEC (now Biogen) - Rituxan (rituximab) was the first antibody therapy approved for cancer. It targets CD20 for patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and pemphigus vulgaris. Rituxan is also frequently used off-label for diseases such as primary thrombocytopenia, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, macroglobulinemia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, Burkitt lymphoma, multiple sclerosis, Wegener granulomatosis, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, bullous dermatoses and hypogammaglobulinemia.

Rituxan got its start from the research (around 1975) of Ronald Levy at Stanford. As a young professor, he worked on a project to develop an antibody against patient-specific surface antibodies (Ig) found on lymphoma cells. In 1981, antibodies discovered from this project were used to treat the first lymphoma patient and around 50 thereafter. In 1985, IDEC Pharmaceuticals was founded to commercialize this research. However, the company couldn’t find a cost-effective way to scale up the personalized treatment and pivoted toward CD20, a more general B-cell target. The premise was to target CD20 to deplete B-cells (normal and malignant) from a patient’s blood and bone marrow while sparing memory B-cells.

After engaging in an antibody discovery project for CD20, a candidate (C2B8) was found. In 1992, an investigational new drug (IND) application was filed with positive data from a phase 1 trial in 1994 (6/15 patients had tumor regression). However, IDEC was struggling to raise more capital to run the clinical trials. The company was developing an entirely new modality, monoclonal antibodies, for an indication that was seen as a small market, NHL with annual cases of around 40K. IDEC’s deal with Genentech in 1995 started off with a lunch and provided the capital necessary to develop Rituxan. After a successful pivotal trial (n=166), Rituxan gained its first FDA approval in NHL in 1997. Subsequent clinical studies showed combining Rituxan with chemotherapy had an even stronger effect and led to its use as a first-line therapy. Even after almost 3 decades since the start of Rituxan’s first trial, the drug is still going strong as a standalone, combination, and maintenance treatment treating around 500K patients per year.

Rituxan was the first monoclonal antibody approved to treat cancer showing the power of more precise medicines - the drug had an almost immediate impact on NHL mortality. The drug also paved the way for the success of other antibody medicines like Herceptin and Avastin. Rituxan also became a pipeline-in-a-pill for several reasons:

Using a new technology, mAbs at the time, to bring more precision to a disease than the standard-of-care. Opportunities in cell therapies, stapled peptides, and gene therapies would be comparables now.

Pursuing an indication(s) with relatively slower progression. This enabled Rituxan to be used for maintenance treatments and have more opportunities to be combined with other therapies.

B-cell depletion has a pretty broad effect in both cancer and autoimmunity, and by creating the first antibody that targets B-cells, Rituxan had the market positioning to see what the effects would be in any disease driven by B-cells.

Source: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.med.59.060906.220345

A more recent example for the pipeline-in-a-pill strategy is Avacopan (CCX168) developed by ChemoCentryx and is close to approval to treat patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. The drug is a C5aR (a complement receptor) antagonist and is also in clinical trials for C3 Glomerulopathy and Hidradenitis Suppurativa. With a mechanism similar to Alexion's Soliris, Avacopan has the potential to treat a wide-range of complement-driven diseases.

Advair, developed by GSK, is a combination of fluticasone (steroid) and salmeterol (bronchodilator) to treat COPD and asthma. The drug acts by relaxing bronchial smooth muscles and reducing overall inflammation. GSK invested heavily in trials to expand use of Advair and was pretty aggressive with off-label use. Another example of a pipeline-in-pill, is Neupogen developed by Amgen. The medicine is a recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). The drug was first approved in 1991 for chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and over the decade and beyond gained approval in aplastic anemia, during a BMT, and more. During chemotherapy and other cancer treatments, a patient’s immune system is essentially destroyed and Neupogen helps stimulate the growth of immune cells to reduce mortality from infections during a treatment program. During its first clinical trial, Amgen established the safety profile and strong neutrophil recovery for Neupogen. This positioned the drug as the standard-of-care for patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Revlimid (lenalidomide) is another interesting example of a pipeline-in-a-pill. Developed by Celgene, the drug was first approved in 2005 to treat myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). In 2006, Revlimid was approved in multiple myeloma, r/r mantle cell lymphoma in 2013, and follicular or marginal zone lymphoma in 2019. The drug came out of Celgene’s research in immunomodulating drugs in the 1990s; interestingly, Revlimid was discovered from phenotypic screening and only after approval was it discovered that the drug engages an E3 ligase to selectively degrade the IKZF1/3 transcription factors.

These 9 examples of drugs that are their own pipelines highlight the enormous patient impact and business scale that the PiP strategy can achieve. Other drugs that have had similar success like Imbruvica and Opdivo are worth mentioning. Companies such as Seattle Genetics, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Aravive, and Kezar Life Sciences are in positions to build similar franchises. There are also opportunities to bring the PiP strategy to other indications like neurodegeneration, aging and age-related disease, and respiratory disease.

Complementary strategies to pipeline-in-a-pill are building a portfolio of assets or a platform. The former focuses on using a diverse product portfolio as the moat and the latter focuses on technology as the moat. Then the pipeline-in-the-pill strategy has the actual drug (and its clinical success) as the moat. If PiP is offense, the portfolio strategy is defense. In a given indication, a suite of drugs across different disease stages can help a company keep sales steady despite new entrants. For portfolio building, large investments in R&D and clinical development must be made. Large companies like Biogen and Pfizer are often the only ones that have the balance sheet to build large enough portfolios. On a sidepoint, some companies are founded to fit into these portfolios and get acquired down-the-line. For Biogen, the company has used partnerships, M&A, and internal development to build a portfolio centered around multiple sclerosis. Pfizer has done something similar for JAK inhibitors; with tofacitinib approved and other candidates approved that have different dosing, formulation, and PK/PD features to diversify the company’s program. A portfolio strategy enables these companies to more easily adapt to changing market conditions and match a product to a particular patient population.

The platform strategy is centered around a new technology and scientific expertise. The major advantage is the ability to attract partnership opportunities. This lowers the cost of capital for a company and their technology’s perceived scarcity can help them garner more favorable deal terms especially if partners feel they are being left behind in a technology revolution. However, drug development is still complex so a platform is limited by our fundamental understanding of biology and disease. Moreover, platforms have historically had a tough time staying relevant over time; there are a few outliers like Adimab and Regeneron. A major milestone for a platform company is clinical proof-of-concept data. The idea is that this can validate the platform’s ability to generate more promising drug candidates. Along the way, a platform company can execute various licensing deals with companies that have more capital and commercial resources. AbCellera executed this strategy to near-perfection. For these platform deals, a partner bears development costs and risks and the company brings the technology and knowhow. Examples of platform technologies are AAVs, RNAi, mRNA, ADCs, and some cell therapies. The premise of platforms is to create a template that generates a series of medicines. Historically, platforms that focus on genetic drivers of disease do the best. An example of a company executing several strategies is Seattle Genetics, which not only has a shot at executing a PiP strategy but has the leading platform for antibody-drug conjugates (ADC). Moreover, Alnylam is the leader in RNAi and has used its platform to build an enduring company with several approved medicines and many more on the way. RNAi, and antisense oligonucleotides in particular, is suited for a platform approach since after the chemical backbone is designed and validated, the sequence targeted can be easily interchanged. As a result, the upfront investment for ASO development can be amortized across more trials. It actually wouldn’t surprise me if Alnylam gets into genomics somehow. Ultimately, the pipeline-in-a-pill strategy often creates the largest outcomes of the 3 approaches. Additionally, new tools from genomics, machine learning, and synthetic biology could make the design of drugs that are their own pipelines more predictable. For founders and inventors, these strategies create 3 main paths: (1) develop an asset with pipeline-in-a-pill potential, (2), build a company to be bought and integrated into a larger portfolio, and (3) use a platform to execute partnerships and make new medicines. The rare company could figure out a way to do all three.