Axial - Veeva

Surveying great inventors and businesses

Axial is really excited to announce our new podcast and first episode with the founders of Unnatural Products, Cameron Pye and Joshua Schwochert on Beyond Undruggable: The Future of Drug Development: https://anchor.fm/axial Be sure to follow us wherever you listen to podcasts as we have an all-star lineup of founders and inventors coming up on the Axial Podcast.

Also, check out the BioBuilder Jobs Board Axial recently launched: https://pallet.xyz/list/axial/jobs If you are a founder or working at a life sciences company, feel free to post any open job postings you have. If you're looking for a job, check out the jobs board and apply to opportunities that would be a fit. Really excited to see this grow and become more useful to everyone.

Axial partners with great founders and inventors. We invest in early-stage life sciences companies such as Appia Bio, Seranova Bio, Think Bioscience, among others often when they are no more than an idea. We are fanatical about helping the rare inventor who is compelled to build their own enduring business. If you or someone you know has a great idea or company in life sciences, Axial would be excited to get to know you and possibly invest in your vision and company. We are excited to be in business with you - email us at info@axialvc.com

Veeva was founded in 2007 by Peter Gassner and Matt Wallach to make life sciences more efficient and bring new medicines to patients. The company is one of the most important case studies on how to build a standalone software business in life sciences. Focused on managing clinical data and communications for life sciences companies, Veeva pioneered the vertical Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) business model by building out one of the first industry-specific clouds.

Peter had previously worked at PeopleSoft and Salesforce before starting Veeva. Matt had built the life sciences business at Siebel Systems, which was acquired by Oracle. And actually, a lot of Veeva’s early customers came through Matt’s network. Furthermore, Veeva’s first product was built on top of Salesforce. Veeva had both lower upfront product development and customer acquisition costs, which enabled the business to scale pretty efficiently. Moreover, these experiences at 3 iconic software companies set the initial conditions for the company: Salesforce was the first pioneer in SaaS and while there, Peter had the idea to make a cloud product specific to an industry. At the time of founding, SaaS was a somewhat controversial business model. A vertical SaaS business was even more controversial and seen as pursuing markets too small to build anything venture-scale. However, Peter had the perfect personality to build Veeva since he never liked to follow the herd. With high regulatory requirements and operating needs and a large product revenue, the life sciences market was a perfect fit for a vertical SaaS product and was still open for Veeva to take over with their CRM product before Salesforce could.

With Veeva, Peter was focused on building a lasting company, and a lasting company “needs a good profit margin.” So he set running a profitable business as an immutable parameter and built around it. Veeva raised $7M in venture capital, only using $3M of it, before going public. This scarcity of capital focused the company across sales, deal making, and team building. Early on in Veeva’s lifespan, Peter only set quarterly goals for the first few years then graduated to annual then 5-year goals as the company grew. Throughout this adventure, Peter was pressured to spend more but he took a conservative approach to minimize dilution and keep Veeva focused.

The life sciences market has a lot of high value customers since they are using Veeva to manage clinical trials for potential billion-dollar drugs. So Veeva’s first customers actually helped fund the company and gave Veeva the ability to generate enough cash flow to make the business sustainable pretty quickly. Peter made sure Veeva did deals clearly with their customers, laying out what is expected from both the product and customer. This is represented in their values that has driven their decision making since founding:

Be frugal with capital and selective with who is hired

Get the product out quick

Sell product at a good price to as big of a customer as possible

Don’t give away professional services (often services are not profitable for most SaaS companies). For Peter, a product comes with a certain amount of services like customer support, training, among others.

These values drove long-term growth for the company. With an addressable market that has customers numbering in the hundreds, not thousands or tens of thousands, each relationship for Veeva matters. For example, Peter has made sure to structure Veeva’s sales team to not maximize topline revenue in the short run. Veeva makes sure not to put too many sales reps in the field or over-cover an area or set of customers with a rep. This is all to make sure the customer doesn’t feel like they are being squeezed to buy more software or services than they need. The company plants seeds to generate sales 4-5 years down-the-line. Things like this weren’t all figured out on day one. Peter and the team had to learn along the way, but their values were the guiding light.

Execution has been the most important part of Veeva (i.e. “Execution is enduring”). Veeva built a foundational software product for life sciences by putting the customer at the center. With over 50% market share in the life sciences customer relationship management (CRM) market, Veeva has proven out the potential of building a vertical SaaS business in life sciences. However, Veeva is working to expand into other industries like cosmetics and industrial chemicals as well as developing other product suites for their life sciences customers. For Peter, “a company that can make its second act bigger than its first act has some long-term ability to reinvent itself.” On this theme, Peter makes it a habit to always think about what he calls the adjacent possible: every 3 weeks or so he engages with someone building software in another industry, a doctor, or someone else adjacent to Veeva’s focus. This helps Peter to avoid becoming myopic, bridge new ideas, and cross-pollinate. I am sure this has helped Veeva to expand its purview and not become stale. This focus on the customer and always staying on the cutting edge has made Veeva one of the best case studies on how to build a large and scalable software business in life sciences.

Key findings

Veeva has built the leading end-to-end software product in life sciences. They are helping make drug development global and removing a lot of operational barriers for a drug to get from the lab to the patient. Veeva is expanding into data and patient relationships and has the potential to build out pretty strong multi-side network effects.

An important part of Veeva’s success was its sales strategy. Because it had a relatively smaller number of customers to sell to, each relationship mattered a lot. The company relied on reference selling where Veeva’s key customers kickstart the sales process to other potential ones.

Veeva used a reverse churn strategy to expand their addressable market. With hundreds of customers, the company had to figure out a way to upsell them without deteriorating their brand. The first step to have a shot at reverse churn is getting lock-in. Veeva does this with integrations, data, and services to increase switching costs for the customer.

Software companies in life sciences will meet at a Milvian Bridge as their product offerings increasingly overlap. Veeva shows that software in highly regulated industries requires different growth strategies. The company used the Salesforce CRM platform and prior relationships to execute a brilliant top-down strategy. There are now develop-driven strategies and increasingly fintech ones to get users. And as the physical world of the lab converges with software, simulated environments may increasingly become a standard. As a result, interoperability, software persistence, and scale across life sciences and healthcare becomes much more important in this scenario.

Technology

Veeva’s first product (Commercial Cloud) was actually built on top of Salesforce. Veeva pays a licensing fee per seat to Salesforce with a ~15% royalty fee and a non-compete agreement to ensure Veeva can’t use its CRM product in non-life sciences’ markets. This type of arrangement helped Veeva efficiently launch their first commercial product. From day one, this type of deal has a large impact on gross margins. But for Veeva this was acceptable to get a faster go-to-market (GTM) and lower initial R&D spend. Veeva started building up product moats by customizing the Salesforce CRM for life sciences companies to manage clinical data from regulatory submissions through commercialization.

So the Veeva Commercial Cloud is essentially Salesforce with add ons built on top. Veeva adds pricing power and a moat with the modules it builds on top of Salesforce rather than the core software itself. More often than not, a new Veeva module (at least 9 right now) for Commercial Cloud can add ~10% to up to 20% more revenue for the product. Think of it as a suite of tools to help drug developers manage their interactions with clinicians, sales representatives, and a lot more. For example, if you’re a sales representative at a large biopharma company, Veeva’s CRM helps you manage your contacts on the clinician side from making appointments, having clinical trial results to show during visits, and engagement through automatic emails. Similarly, the CRM helps people doing clinical research manage patient relationships and data. So the software platform spans everything from marketing, sales to collaboration and data management. This CRM forms the basis of Vault, Veeva’s 2nd and larger product.

Now, Commercial Cloud represents a little under half of Veeva’s revenue while Vault makes up over 50%. This is pretty rare - a company’s second product that is larger than its first. Roughly, Commercial Cloud dominates late-stage/post-market activity, while Vault is the standard for earlier stage work. The major inflection point for Veeva was around 2010 when they decided they wanted to become a multi-product company. Vault, launched in 2012, is a content management system that helps users organize their various documents and workflows from clinical trials to manufacturing and sales. And Veeva built their own infrastructure for this. The CRM helped enable Vault by allowing Veeva to use a reverse churn strategy and upsell existing customers rather than solely find new ones. Moreover, Veeva’s initial success with its CRM was driven by replacement cycles for Siebel systems and a general move to the cloud. Similarly, Vault just replaced a lot of the old content management systems life sciences companies were using.

Content management was a market with a lot of single-client hosted products that were often on-premise. Vault was built to be a unified cloud version. Veeva generates pricing power here by offering individual applications (i.e. regulatory, marketing) for Vault or an all-in-one pack:

Commercial Content Management - puts every document within a life sciences company in one place and allows the user to manage which people get access to certain data and have a lot more visibility on various processes from trials to sales and manufacturing.

Development Cloud - allows the user to build new applications like standard operating procedures (SOP) to new manufacturing protocols.

Safety - helps users maintain compliance across their product development cycles and ensure pharmacovigilance.

Medical Device Suite - focused tools for medical device development, quality control, and commercial rollouts.

Vault’s subscription revenue is well over $500M growing >40% over the last 4 years. Veeva took a similar strategy, as with its CRM, to use modules to increase Vault’s growth. Without paying Salesforce a royalty fee and as Vault becomes a larger part of Veeva’s business, their margins ought to increase significantly. Ultimately, Vault allowed Veeva to expand the universe of companies it can sell to. With Commercial Cloud, Veeva could sell to the 500 or so life sciences companies with a commercial product. Vault allowed the company to sell to well over 10,000 life sciences companies in earlier stages of R&D and product development. The company went public in 2013 and since then Vault has become its crown jewel. Around 2016/2017, Veeva expanded its purview to help patients too: finding the right clinical trial and driving new medicines forward.

Veeva uses its CRM and Vault product as a platform for next-generation products. Right now, its focus is on data and patient-facing products. Veeva has built out Network, OpenData, and Data Cloud to manage master data, connect to reference data, and provide access to patient/prescriber data, respectively:

Network - a centralized hub for customer data.

OpenData - connects partners with a validated reference data set on patients, clinicians, and more.

Data Cloud - a large dataset of patients and drug prescribers in the US; Veeva makes this data available to drug companies. Recent M&A from Veeva buying Crossix Solutions and Physicians World supports their strategy to become dominant in offering data to their customers.

Veeva is also moving toward engaging the patient. MyVeeva is a platform to connect physicians and patients with life sciences companies. For physicians, the application allows them to more easily communicate with trial sites, healthcare liaisons, and sales people. On the patient side, MyVeeva allows them to more easily connect with clinical trials and complete consent forms. This all leads to Veeva gaining more momentum in decentralized clinical trials and expanding their customers’ ability to engage patients and sell to healthcare professionals. From Vault to these new products, Veeva has focused on reverse churn and building a fully-integrated product suite in order to build substantial moats across the entire user experience.

Veeva, the founders, and the entire team have done an incredible job to build enduring software products in life sciences. There are some lessons that can’t be replicated and a few that can:

Lower technology development costs - Veeva handed over ~15% of its CRM revenue to build its life sciences applications on Salesforce’s platform. This helped reduce the capital required for Veeva to launch. There might be opportunities to do something similar today on top of a platform like Snowflake.

Lower customer acquisition costs - most of Veeva’s early sales win came from Peter and Matt’s network. They were essentially replacing older on-premise software from Siebel/Oracle and IMS Health with Commercial Cloud.

The move to the cloud - a major tailwind for Veeva over the last decade and more has been getting life sciences companies off client-side software and into cloud applications.

Bundling software to gain pricing power - in life sciences, content management and approval were separate from customer relationship management. Veeva has built out Vault and its CRM and removed a bunch of friction and manual processes in drug development.

Built a moat around the services - beyond software, a major advantage for Veeva has been the consulting and business services wrapped around Commercial Cloud and Vault. The company has dedicated teams to help customers build extra functionality on top of Veeva’s platform focusing on commercial applications like GTM strategies and salesforce optimization.

Veeva has built the leading end-to-end software product in life sciences. They are helping make drug development global and removing a lot of operational barriers for a drug to get from the lab to the patient. Veeva is expanding into data and patient relationships and has the potential to build out pretty strong multi-side network effects.

Market

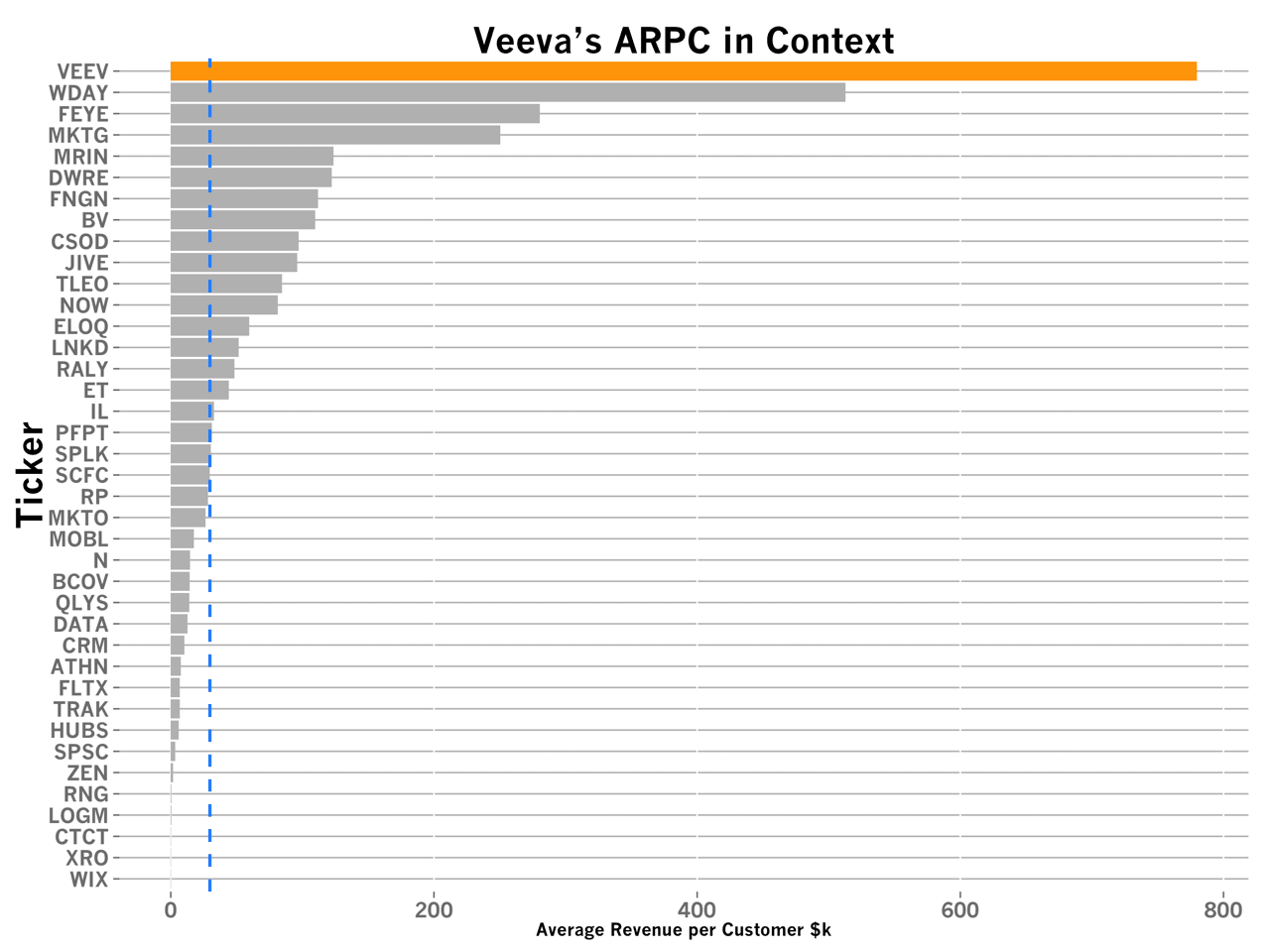

Veeva has been very useful to me as a general way to measure the number of companies in life sciences and the size of the software market in the vertical. As of the beginning of 2021, Veeva had 993 customers ranging from Gilead and Merck to Alnylam and Moderna. Across their two main product lines, Commercial Cloud and Vault, Veeva generates around $1.17M subscription revenue per customer (an outdated image below showing how much Veeva is an outlier compared to other SaaS companies). With the former having around/over 432 customers and Vault with 852. In 2014, Veeva estimated that the addressable market for their software products was around $2B for both its CRM and Vault. In 2021, the company estimated that the market size for Commercial Cloud had increased to ~$3B and Vault to $5B. Overall, well over $100B is spent per year on clinical trials.

Veeva has dominated both the CRM and content management market in life sciences (with well over 50% market share) by “[making] sure the market is clear then [figuring] out if it's correct later on.” In short, Veeva focuses on markets where there is a lot of spend. For clinical trials, it’s over $100B. Elsewhere in life sciences, over $4B is spent on pre-clinical research along with a ~$1T chemicals market and $10Bs being spent on biomanufacturing annually. Veeva’s focus on a specific vertical (life sciences) narrowed down the number of customers they can sell too - hundreds/thousands versus 10,000s for generalist SaaS companies. An important feature of the life sciences market that helped Veeva is how concentrated the market is: the top 50 companies account for over 70% of sales. The smaller market allowed Veeva to build products that embrace the complexity and regulatory requirements of drug development where others, like for example Salesforce, avoided initially to grow in less obtrusive markets.

An important part of Veeva’s success was its sales strategy. Because it had a relatively smaller number of customers to sell to, each relationship mattered a lot. The company relied on reference selling where Veeva’s key customers kickstart the sales process to other potential ones. So for a given product line, Veeva starts off with a smaller number of early adopters. Once these customers are successful, Veeva converts them into vocal advocates mainly by using their success as a case study for others. This is connected to how Veeva structures its sales team. The company has to ensure it doesn’t oversaturate their customers with sales pitches at risk of alienating their already small customer base. The overarching theme here is “engaged teams working together”:

Sales are not measured quarterly at Veeva for things like bonuses. There is a focus on hiring to set up sales down-the-line. But this type of approach requires disciplined product planning, and with Peter being Swiss-American, he makes sure the trains run on time at Veeva. Historically, the company has been great at knowing where their products are on the adoption curve. For example, the CRM has over 80% penetration for biopharma whereas MyVeeva is still early. This influences how Veeva’s incentives sales and structures teams.

Trusting other teams within Veeva, which is very hard for any company at scale. Their sales incentives play a big role in the organization’s cohesiveness.

The sales team focuses on early adopters within a company in order to find a champion and set up their reference sales model (i.e. get early adopters and spread success stories)

Having a bias toward organic growth.

Spending money like it’s your own - for example, Veeva has no travel expense policy. Peter flies coach, which saves Veeva a few million dollars per year, but others aren’t forced to do the same. The founder is just leading by example.

These types of values all increase the stature of Veeva’s brand in the eyes of its customers. So in life sciences with large markets but a smaller customer base, trust and branding are way more important. Veeva is now exploring new markets beyond drug development towards consumer goods, chemicals, and cosmetics. As the life sciences ecosystem becomes larger and more diverse (i.e. emergence of synthetic biology), more pure-play software companies in the field might become venture scale.

Business model

Veeva was one of the first vertical SaaS companies. Salesforce was the pioneer for SaaS and paved the way for the business model shift from perpetual software licenses to subscriptions. But Veeva extended this SaaS model to a specific industry, beating Salesforce to the life sciences. In the early-to-mid 2000s, most SaaS companies were focused on problems across multiple industries in order to maximize total addressable market. At the time focusing on one market seemed a little unwise. Would customers be willing to pay a premium for software? How much? Despite the small customer base for a vertical SaaS business, there are major advantages in higher sales efficiencies by going to the same customer and selling them more overtime:

Lower customer acquisition costs - Veeva’s sales and marketing team can tailor their story to specific customers unlike other SaaS companies. This can lead to lower costs overall and higher conversion rates. Sales and marketing represents around 20% of Veeva’s sales whereas other SaaS companies range from 30%-50%.

Deeper product development - Veeva can also invest more resources into building software with functionality specific to life sciences. Veeva builds software for an industry with high regulatory requirements, everything from QA to clinical data and sales engagement. Sometimes the product needs to be customized for one customer; this is where services become a major advantage. Also, vertical SaaS actually enables faster product development and allows a company to build product moats through add-ons and integrations creating up/cross-selling opportunities and increasing switching costs.

Knowing your customer better - having less customers to sell to allows Veeva to really get to know them versus the comparable, horizontal SaaS company.

Very high capital efficiency - Veeva is an outlier in terms of LTV/CAC. With lower CAC and a stickier product (increases LTV), Veeva compensates for a smaller customer base with a highly efficient business model. Veeva’s CAC has historically been between 0.8 and 1.2 whereas other SaaS companies are often at 1.5 and up to 3. Veeva has been so successful here due to its reference selling model and focus on life sciences. For vertical SaaS companies, unit economics becomes a much more important metric than sales growth. In short, every customer counts in vertical SaaS. Unit economic metrics are invariant to time so it’s really important to think how something like CAC or LTV (and their various sub-components) scale. Hiring a salesforce scales a lot differently than spending money on Instagram ads, but both contribute to CAC. For markets that have less customers, like life sciences, CAC will quickly increase as spending goes up. As a result, branding and how your customer perceives your product is probably the most important part of any vertical SaaS company.

Vertical SaaS is risky because a company is putting all their eggs in one basket. You have to be really good at picking the right markets (i.e. clear then correct). The market chosen might slow down in growth or there could be some sort of regulatory change that makes product development harder.

SaaS has been the major shift in how software is distributed over the last decade or so. What’s next on the horizon for companies like Veeva? Developer led sales (i.e. bottom-up) led by companies like Twilio has been a major shift. Benchling has led the way to execute this strategy in life sciences. There’s a growing opportunity to combine the increasing power of fintech with life sciences. A company like Veeva does pretty well selling its CRM, content management system, among other products. However, there is a much larger market in life sciences or any industry in financial services or other types of transactions. Vertical SaaS companies are often tightly integrated enough with their customers to expand into things like equipment purchases, lending, payments, and even payroll. In life sciences, there are opportunities to build software for biobonds, services payments, drug pricing, and a lot more. Veeva’s focus on life sciences allowed the company to be much more efficient and more quickly broaden its product portfolio. Ultimately, Veeva focuses all its resources toward a homogenous customer base with the same problems and once they solve them for one, everyone else comes to Veeva and they become the standard.

Veeva used a reverse churn strategy to expand their addressable market. With hundreds of customers, the company had to figure out a way to upsell them without deteriorating their brand. The first step to have a shot at reverse churn is getting lock-in. Veeva does this with integrations, data, and services to increase switching costs for the customer. On a side note, Oracle and DB2 are the epitome of switching costs. Veeva takes a less extreme approach, but once a customer is using one of Veeva’s products, they generate data on the software platform that becomes increasingly hard to transfer over to another CRM or software vendor. But data is probably the weakest strategy because at the end of the day, a SaaS application is at its core just a relational database and a website that presents the data. Most database architectures are the same so it’s hard but not impossible for a customer to transfer data (i.e. ETL).

The modules Veeva builds on top of Commercial Cloud and Vault to create closer integrations with the customer and services that customize the product and add sunk costs through training and time spent to learn Veeva. The company is also building out products with network effects that can also increase its lock-in. For example, Site Connect helps clinical trial sites and sponsors share data. As this network grows, the platform can become the standard for any clinical trial, but this is still early days here. With a lot of customer data, Veeva is in a great position to build new networks, think LinkedIn for drug developers or an ecosystem similar to Apple’s App Store, in life sciences and forge long-lasting barriers to entry. With a smaller market, vertical SaaS requires a differentiated strategy, especially on GTM in order to win a larger share of a relatively smaller market.

Veeva uses software add-ons and services to build a powerful moat around its business. The company has a pretty high retention rate (over 120%) versus other SaaS companies due to Veeva’s ability to create new modules on top of their platform. In life sciences, this type of approach makes sense because companies’ needs evolve as they go through the life cycle of early stage discovery to the clinic and finally commercial. This gives Veeva a lot of opportunities to sell into an organization - they can sell Vault to a company that is just starting up a clinical trial or push its CRM to a commercial-stage company. For Veeva, services are a first-class citizen: their customers “like [their] products, [but] love [their] people.” Veeva builds out software similar to Salesforce or Google, but also has built out an underlying product offering with similarities to Accenture. In short, Veeva builds great software and uses services to cross-pollinate across a company(s) and create lock-in.

Veeva might be impossible to replicate. They had great timing with SaaS just starting off when the company was founded along with the tectonic shift to the cloud as a major tailwind. The founder’s relationships with Salesforce and other companies was also an important initial advantage, and ultimately, most software companies can’t charge over $1M per customer. There are opportunities in bottom-up approaches in life sciences, merging fintech with life sciences, and using a large user base to build new, downstream applications. Most pure-play software companies in life sciences may not be venture-scale due to the smaller number of customers. Veeva is probably the exception. But there are other pathways to use software as an on-ramp to expand into products and business models.

What other opportunities are there for SaaS companies in life sciences? There’s many different types of software companies that can be built here:

Incumbents (to be disrupted or partnered with): ArisGlobal, Bioclinica, Medidata, PerkinElmer, IQVIA. In particular, IQVIA has a pretty expansive product offering as a result of its creation from the merger of IMS Health (clinical data) and Quintiles (a CRO) in 2016. And the company makes it pretty difficult to port datasets into other software platforms. Veeva is actually in a suit with IQVIA over this.

Experimental design and execution: Benchling, Synthace, TetraScience, Elemental Machines, Labstep. The beachhead is design with the long-term ability to start automating the lab.

Data management: LatchBio, EtaBio, ScienceIO, SevenBridges, Elucidata. Files in life sciences are pretty large. We need better tools to query and analyze them.

Clinical trials: Tilda Research, TrialSpark, Unlearn, Science 37, Faro Health. Some important themes here are standardizing sites with Tilda leading the way, new trial designs like synthetic controls and adaptive trials, and patient consented data to more easily scale trials.

Data brokers: Evidation Health, Hume AI, H1 Insights, Komodo Health, Change Healthcare, Datavant, Definitive Healthcare, and even companies like 23andMe, Omica, and 54Gene. Evidation’s recent deal with Merck highlights the power of a data platform to enable new treatments and products in life sciences. Komodo is very fascinating too because they purchase medical claims and patient data and repackage it into new products focusing on recommendations for their customers. The important part of these products are de-identifying and standardizing the data. Even large tech companies have done interesting work here with Apple’s ResearchKit to enable the use of Apple products in health studies and Verily’s Project Baseline that is creating a very large dataset on patients across time.

Marketplaces: BenchSci, Abcam, Science Exchange, Knowde. This type of model is a strong way to monetize transactional volume in life sciences instead of charging a subscription fee for a piece of software.

Clinical tools: SOPHiA Genetics (maybe the best success stories for a SaaS business in genomic analysis; I would recommend reading their F-1), which deserves its own case study, Sema4, SolveBio, Viz.ai, PathAI. Showing clinical utility is a high bar along with the long sales cycles into hospitals and healthcare networks.

Some ideas for pure-play software companies in life sciences (email us if you’re a founder or a builder interested) are:

Software for biomanufacturing. Medicines and biological products are becoming increasingly similar to rocket engines and we need better software to aggregate suppliers and components for things like cell and gene therapies.

Drivers to connect lab devices with software. Synthace has shown the way but this is a large opportunity to standardize data regardless of the OEM.

Build a life sciences company on top of Snowflake similar to building on top of Salesforce to create high-performance computing applications for life sciences. There’s also an opportunity to build a life sciences company on top of Domino Data Lab (thanks Leon) and even a data store like Veeva.

Common interfaces and user experiences especially for open source software in life sciences.

New clinical trial protocol designs. Unlearn has led the way here but there are so many more opportunities.

A calendar for experiments. Some sort of scheduler for the lab and even clinical trials can automate a lot of the upfront planning currently done. Veeva, Benchling, among others are doing this in some way but there might be a window for a standalone product here. Think Zapier for the life sciences lab.

Software companies in life sciences will meet at a Milvian Bridge as their product offerings increasingly overlap. Veeva shows that software in highly regulated industries requires different growth strategies. The company used the Salesforce CRM platform and prior relationships to execute a brilliant top-down strategy. There are now develop-driven strategies and increasingly fintech ones to get users. And as the physical world of the lab converges with software, simulated environments may increasingly become a standard. As a result, interoperability, software persistence, and scale across life sciences and healthcare becomes much more important in this scenario.

Veeva is likely a major exception in life sciences. A few rules might be:

Never get involved in a land war in Asia.

Never go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line.

Never build a standalone software company in life sciences.

But there always exists a lot of interesting opportunities in the long tail. Narrowly-targeted software and products can create very efficient businesses. In some of these niches software might be venture-scale, and even if it isn’t, it can be a user on-ramp to something larger and more meaningful.

Special thanks to Leon Furchtgott as well as others kind enough to review, offer ideas, and provide feedback on this piece.