Build with Axial: https://axial22.axialvc.com/

Axial partners with great founders and inventors. We invest in early-stage life sciences companies such as Appia Bio, Seranova Bio, Delix Therapeutics, Simcha Therapeutics, among others often when they are no more than an idea. We are fanatical about helping the rare inventor who is compelled to build their own enduring business. If you or someone you know has a great idea or company in life sciences, Axial would be excited to get to know you and possibly invest in your vision and company . We are excited to be in business with you - email us at info@axialvc.com

Exscientia is one of the first, if not the first, AI-centered drug development company. Founded in 2012 by Andrew Hopkins out of the University of Dundee, the company worked to translate work around automating design of drug candidates. Exscientia’s unique profile and “network” business model seems to be heavily influenced by Hopkins’ unique career starting at Pfizer then going back to academia at Dundee and then making the full loop by going back to industry, only now founding his own company.

The career of Hopkins and the initial conditions of the company have heavily influenced Exscientia’s business model and long-term vision. The company is the epitome of a founder-led business in biotech. Hopkins, as founder and CEO, still owns over 15% of his company. Pretty remarkable and makes Exscientia a case study worth digging into.

Hopkins first job was at a British Steel plant over summer. While there he discovered his love for chemistry and ended up attending the University of Manchester with a scholarship from British Steel. After graduation, Hopkins went to work at British Steel for a year, a requirement of his scholarship, but then left to join the Stuart Lab at Oxford. During his first stint in academic research, he focused on structure-based drug design for HIV. This left a massive imprint on Hopkins and Exscientia: informing the design of a drug from an evolutionary understanding of disease. Then he left academia to join Pfizer. While there, Hopkins picked up more knowledge about drug development, the impact of genomics and data, and uncovering new problems around drug design that were emerging. Interestingly, he went back to academia at Dundee, going from Kent to north Scotland - a massive career risk, to focus on the application of machine learning on drug design. There and back again. Exscientia was decades in the making.

With a wide network in pharma built over decades and knowing the value of a dollar (or a pound) probably from his experience at British Steel, Hopkins initially funded Exscientia with research projects working with Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Sunovion (part of Sumitomo). These projects generated non-dilutive capital allowing Hopkins to retain more of his ownership over time. For any company seriously using AI in life sciences, scaling the platform and building out an interdisciplinary team are the first steps before any real drug discovery work can be done. As a result, these seemingly small deals set up Exscientia to think long-term in terms of ownership and vision and let their business model grow organically. Exscientia grew into a hybrid of a technology and drug discovery company. Their platform is focused on going from an idea to a clinical asset quickly. There is still so much work to do. But Exscientia, Andrew and the entire team have done an incredible job to implement their drug factory. Like a steel plant creates skyscrapers for centuries, Exscientia is now focused inventing enduring medicines.

The first slide of the public deck lays out the biological hypothesis for Exscientia: build models centered around human data. Automating various processes, focusing on indications where there may be a genetic cause or a well characterized mechanism-of-action (MoA), and building a scaled pipeline are the 3 drivers for the company’s platform. And I’m sure this was figured out over the years and not part of the initial plan. All great companies, and founders, constantly reinvent themselves in small ways.

Overall, lowering the cost to do an experiment enables more innovation. From Hopkins:

“If we can reduce the economic barriers between the start of an idea and testing a candidate in humans, then overall we believe we can speed up the whole innovation cycle.”

The next slide focuses on differentiators. In any pitch, it’s really important to convey your position in the ecosystem within 5 minutes. For Exscientia, they’ve been able to generate a clinical candidate (testing in Japan for OCD) and build out an engine that is productive at generating early leads. Within the subset of AI drug companies, only Recursion and a few others have the technology platform and team set up with the line-of-sight to more clinical candidates. The next decade will determine the winners and losers here. For all these companies, the key metric is not only generating a lot of higher quality leads quickly but ending clinical programs probably just as quickly.

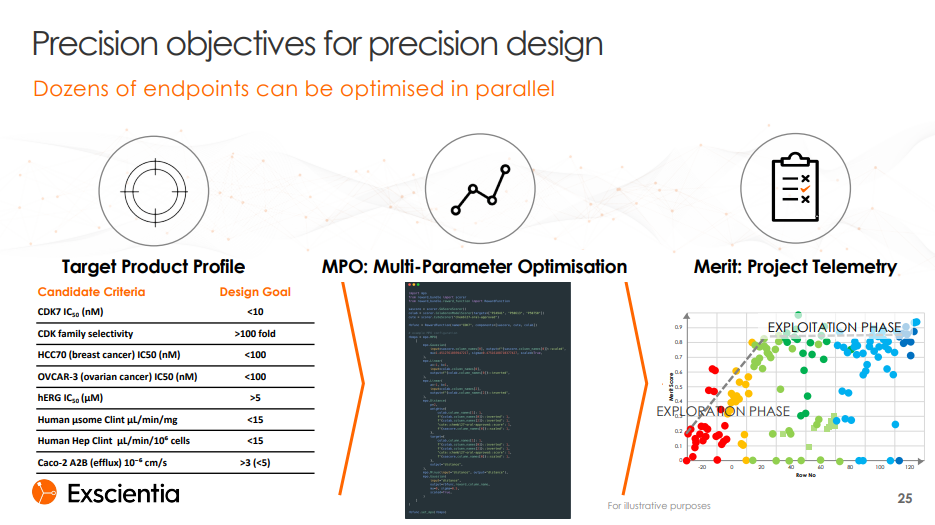

Later in the presentation, Exscientia showed interesting data for a drug candidate of theirs, EXS617, which is a CDK7 inhibitor jointly developed with GT Apeiron. What’s pretty impressive, is the speed at which they developed not only a hit but a drug candidate with comparable features to clinical candidates. At the very least, Exscientia has a platform to execute a fast follower model. Their strategic collaboration with EQRx makes a lot more sense with the context of this table.

After explaining why the company is differentiated, Exscientia lays out their set of partnerships. A lot of biobucks - at least an order of magnitude more than cash paid upfront. There’s so much left to be done. A slide like this immediately reminds me of Millennium and the genomics era of the 1990s. Hopkins was at Pfizer during this time and I’m sure got to see a glimpse of these companies and likely heavily influenced Exscientia’s current model. Ultimately, most of Millennium’s terminal value came from M&A. Just like Millennium, Exscientia is taking their shot with its platform but the company has already shown a willingness to buy other companies when appropriate: Kinetic Discovery to add structural biophysics capabilities and Allycyte for its patient data and processing abilities. With an excess of platforms creating too many assets, wise companies will use their platforms & balance sheets to find undervalued drug candidates that might end up being worth more than the platform itself.

The next slide goes into the progress across these partnerships. On a side note, you might not be the iconic “next-gen” drug company if you don’t have a deal with Bayer. Millennium had a large one - using the deal to stack more down-the-line. And Exscientia seems to be doing something similar.

The recent Sanofi deal is pretty significant for Exscientia. Platform-partner fit is really important and distinct from product-market fit. A deal like this validates the value of Exscientia’s platform and if used well, will allow larger deals to come. The key lesson in biotech BD is always narrow deals. I’m sure Exscientia could strike up a CNS deal with Biogen and a cardiovascular one with Novartis.

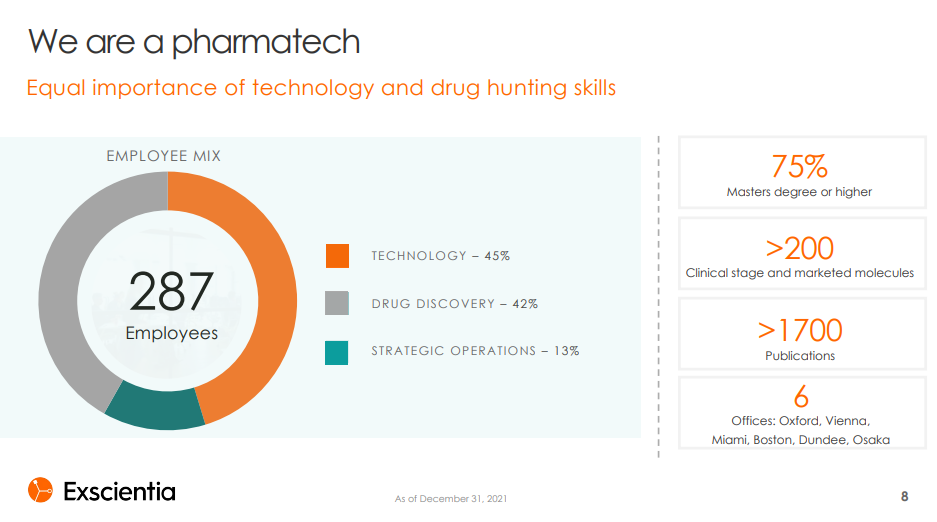

To build out this platform, Exscientia has to be world-class at both drug discovery and technology. A common refrain in the field is to brag that you have more engineers than scientists. For Exscientia, they are roughly 50/50 for people building tech versus designing drugs. The hard part is getting these two groups to work cohesively. The dynamic is similar to quants and traders on Wall Street.

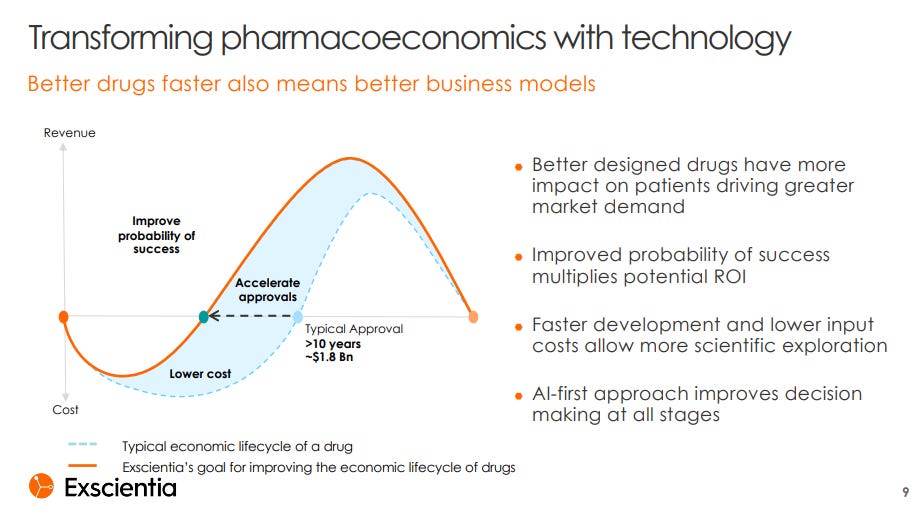

This is probably the most profound slide in the deck. By developing clinical candidates faster, there is an opportunity to change the cost structure of drug development. By moving faster, you could potentially save some amount of money. The amount is controversial and still to be determined: is it ~$20M or in the $100Ms? If you move faster into the clinic and the drug candidate is approved, you’ll get cash sooner. And cash has a time-value. So the premise of putting higher-quality candidates into the clinic at a faster rate could lead to scalable biotech business models. The crux is rationally figuring out which programs to end (it’s more cultural than intellectual) and making sure you’re responsibly putting drugs into humans. Given the latter limitation, this model might work much better for known targets and well-characterized diseases.

Results so far: Exscientia is good at developing candidates within a year. Excited to see the clinical results. Whether these drugs are successful or not is not as important as how the company manages this portfolio and learns from success and failure.

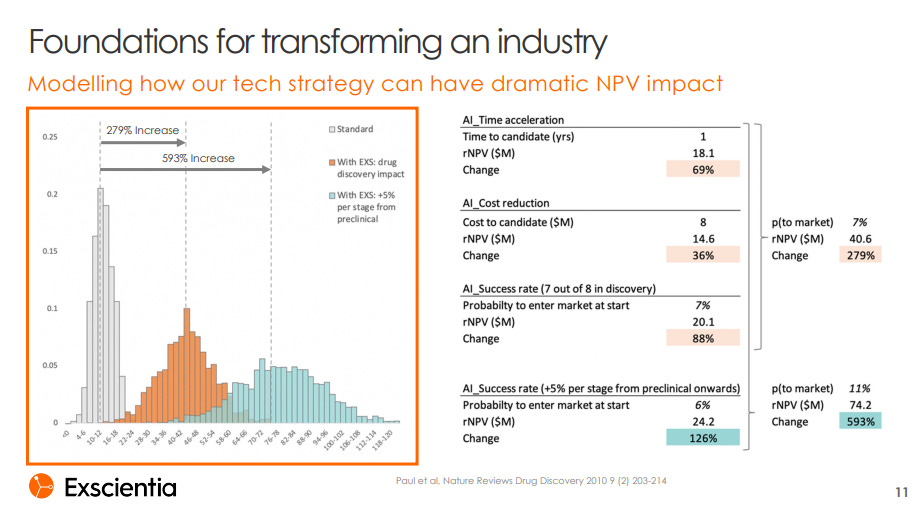

Exscientia includes an interesting financial model. The takeaway is that moving faster (<12 months) and reducing costs to generate candidates can lead to an at least 2x higher NPV of a given program. The success rate metrics might be subjective and would be worth a deeper discussion around.

Pipeline updates. There’s no reason Exscientia can’t have >100 programs within a decade. Most won’t work but some will. Drug development is a top-of-the-funnel problem. Just put high-quality candidates at the top and with the same odds, you’ll have more medicines.

The company has a large number of leads. How do these get funded and developed in the clinic? That’s where a business model becomes important. Also, companies like Exscientia are best positioned to develop biobonds and start a revolution in securitization (i.e. fintech meets biotech). Ultimately, enduring platform companies will be automated and show an ability to end a large number of early-stage programs.

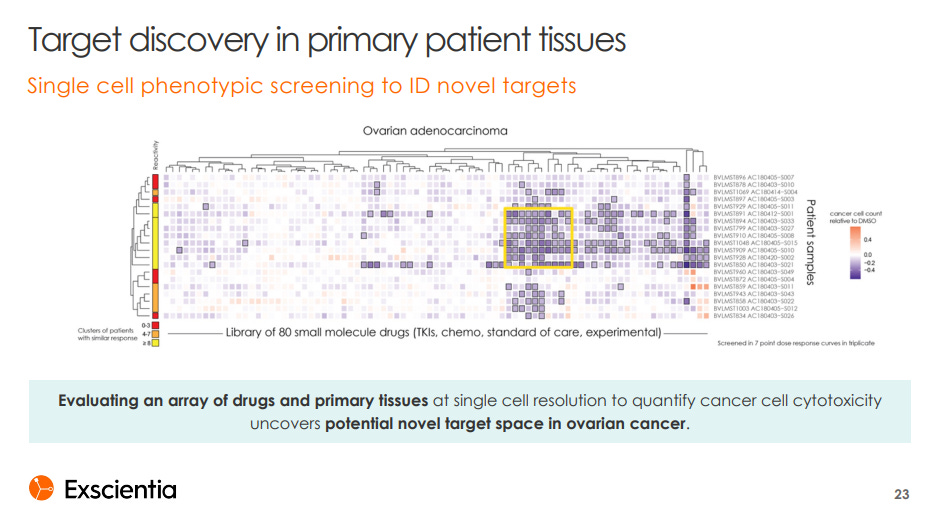

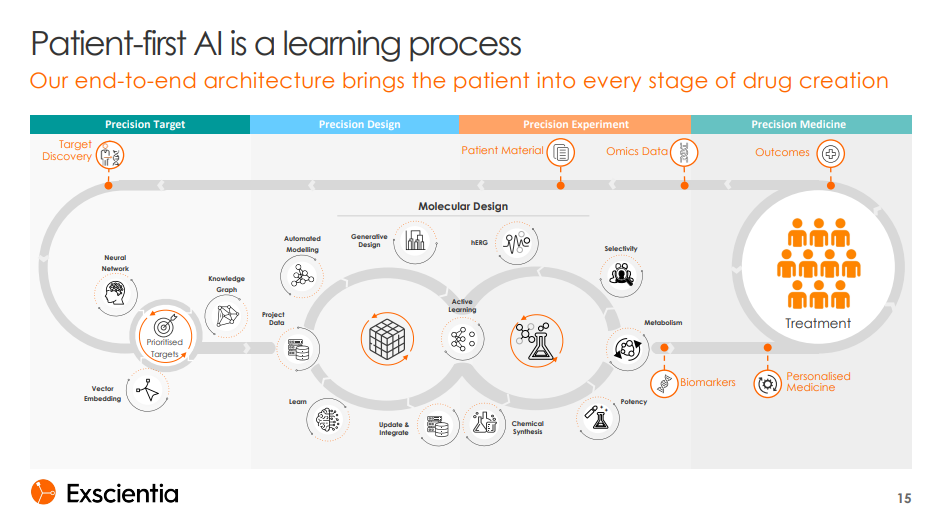

The next slide goes back to the biological hypothesis. By building the machine that builds the machine, Exscientia will get close to a point where patient data can be collected and analyzed and high quality leads generated. Medchem is always needed but AI will augment the best and speed up this entire process. A platform like this could increase the bandwidth of a great drug developer and massively improve their productivity.

This graphic is a fancy workflow representing the platform. Kind of reminds me of The Game of Life board game. Exscientia calls their platform Centaur to represent the merging of AI and human decision making. On a side note, Elk was my nickname on my high school football team. But then it morphed into also calling me Centaur and I never really liked that nickname. My senior year, when my teammates found out I was doing well in school, they started making more lewd variants of the Centaur name.

Like all leading life sciences companies using AI, standardizing data generation might be the most important moat. You need a platform that can do the unphysical experiment.

The last slide goes into milestones. The first slide or two is where a company lies in the ecosystem. The last one is often on team or milestones. In my opinion, Exscientia’s ability and courage to end programs will signal to me that their model of moving faster into the clinic might end up working.

Also, the name of the company has a cool origin. The motto of the US Navy is “ex scientia tridens” which means “from knowledge comes sea power.” Really interesting that a Brit took something from a Yankee. Exscientia is more like “ex scientia medicinae.” From knowledge comes medicines.

Hopkins didn’t let his group’s work end at a paper. By founding Exscientia, he mobilized a lot of talent in the UK and inspired a new generation of biotech founders. Hopkins had incredible founder-market fit here. By switching between academia and industry several times throughout his career, he had the expertise to do something different but knowledgebase and network to know the value of his group’s work and what the important problems are. Coming out of the genomics boom in the early 2000s, having high quality structure-activity relationship (SAR) data and more easily connecting screening data to compounds was needed. This likely helped Hopkins establish his lab’s research program at Dundee that ultimately led to Exscientia.

By building a platform to go from years to months to enter the clinic, Exscientia could lower the barriers for breakthrough research, often out of academia, to be tested. I wouldn’t be surprised if Hopkins makes a 3rd visit to academia. He’s probably not going to leave his company but I would bet Exscientia will forge some sort of research partnerships with universities.

Lastly, a useful heuristic is: biology is unpredictable and chemistry is predictable. So Exscientia has shown an ability to find chemical matter for kinases and other validated targets. I think some of their earlier-stage programs are taking more target risk. Biology is still really complex. That’s what makes it beautiful. Exscientia is focused on bringing more clinically-relevant data earlier into the drug discovery process to deal with this unpredictability. But like all biotech companies, unmeasured or unexpected biology leads to a clinical failure. How a company responds to early results and data often matters a lot more than the individual event. With a valuable platform and diversified pipeline, Exscientia is in a good position to build a business to last and inspire.