Observations #1

Every Friday morning a set of ideas and observations from a week’s worth of work analyzing businesses and technologies.

Life sciences is finally getting plugged into the capital markets

After a dinner with a few banker friends a few nights ago, I realized two things: bankers have a really tough lifestyle that might not be worth it and life sciences is actually not connected to capital markets. A drug company can raise a good amount money and increasingly so (i.e. Sana, GRAIL); however, when compared to industries to oil or infrastructure, financing in biotech and life sciences in general looks a little prehistoric. Drug development and most work in life sciences is underwritten through equity. It makes sense given the high-risk nature of the businesses and the flexibility of equity. But companies in movies or oil drilling can often be just as risky as a RNAi company. However, the former can more easily get access to a $100T US corporate debt market, while the latter is confined to a $30T US public equity market. That’s some money left on the table.

In life sciences, there are examples of companies issuing debt, but it’s either from desperation, a small cap on its last leg, or a vulture-type of situation. But all-in-all, the terms are not that good and the underwriters don’t have the sophistication of say KKR or Blackstone. But thankfully for the field, these types of investment firms are now beginning to enter the fray. Maybe due to lower returns elsewhere or a deeper appreciation biology’s power, but for whatever the reasons, it is really exciting times for how a life science company will get financed.

Life sciences is catching up to the rest-of-the world in terms of capital markets - with examples like BridgeBio and maybe Syncona and Cydan, companies are getting more sophisticated in terms of measuring risk in their product portfolio and matching the proper financing with it. Instead of just doing equity because everyone else is doing it, successful companies are figuring out where debt is appropriate; what’s advantageous is that debt is non-dilutive and there’s a lot of it as favorable terms. Hard part sometimes is making sure you have the money to pay it on time. As new tools like AI and a general increase in know-how, it’s plausible that work in biology becomes more predictable and is more amenable to debt financing. This is historically a treacherous path - leverage has driven almost every bubble in some way, but if a company like BridgeBio can do it successfully and become a $100B business, life sciences will finally get up to speed on capital markets.

Drug prices and tales of Peak Pharma

From the perspective of an outsider, drug development as is looks broken. Media tells you drug prices are too high, comedians tell you that there’s no money in curing people, and you probably have never met a scientist. To someone in the field, it has been puzzling on why there is so many attacks on new medicines. The business model of buying existing drugs and jacking up prices beyond the value they generate is immoral. But there’s all of these new medicines from Keytruda, to gene therapies, and many other modalities coming to patients that massively increase the quality of life and sometimes bring cures. That’s worth a lot and should be rewarded. Often, a medicine is the best way to deliver healthcare - little to no human involvement and you keep a patient out of the hospital, a major cost center:

From doing some analysis on Regeneron into earnings and trying to figure out how big their cholesterol drug, Praluent can get, I encountered a non-profit called The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). They are playing a important role in determining drug prices for their value. I haven’t spent the time to dig into their models and methodology and make sure they’re improperly incentives (i.e. payments in the backend from a drug lobbying group), but the general idea of pricing a new medicine for its value is very powerful. The general shift to fee-for-value in the US healthcare system will enable new business models (i.e. make infectious disease work lucrative, new types of clinical networks).

In parallel, the efficiency of making a new medicine overall has been decreasing. This is driven by quite a few factors, one major driver is overall incentives in the industry. There’s no shortage of breakthroughs in life sciences (image below), but a medicine curing a disease or making a major dent in a very difficult indication is not being properly rewarded right now to incentive investment toward them.

Research and incentives

Perusing through Hacker News once in a while brings a gem - https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=21388715 - a good article in Scientific American explored what type of scientific research, most of the time poor, the US academic system is incentivizing. If you’re an assistant professor at Ohio State or UC Irvine, you need money to support a lab. Most grants are very competitive and incentivize PIs to go after sexy projects or do experiments that sound exciting but don’t solve core problems. Researchers at institutions like Harvard and Stanford are protected a little bit more from this type of influence - in short, money is not as tight. This leads to a power law effect for inventors. A small portion of the population are great inventors and can consistently produce sterling data. It’s not because they are much smarter but are rewarded to conduct research for a long-term impact no matter the short perceptions.

As an investor, finding an inventor who has somehow detached themselves of the overall incentive structure of academia is incredible compelling. Their work is going to be high quality and the investor’s job is to help design a business model around the inventor and their inventions. All of these big problems like Alzheimer’s, sustainable materials, energy, aging, and on and on and on will be solved by a great inventor not an investor, a Twitter fiend, or anybody else.

Food production and incentives

The New York Times ran a really interesting article this week - https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/03/world/europe/eu-farm-subsidy-hungary.html Similarly on incentives, on we produce food on a global scale is unsustainable. Companies like Pivot Bio, Pairwise, and AgBiome led by great founders will be the driving force to solve this. It's probably not going to be governments because they are getting paid off. Growers have little to no say. So it’s up to businesses to empower growers and give them new tools to succeed despite the overall system and hopefully that in itself leads to change.

Aromatherapies

A few days in the morning when I was riding the stationary bike, I was reading the Wall Street Journal and came across an intriguing and weird article on inhalable vitamins. In the backdrop of Juul and the massive public health crisis, quite a few companies like Ripple, MONQ, Inhale Health, and Kinin have sprung up to use similar technology as Juul but focused on vitamins and essential oils instead of nicotine. I really don’t have a strong grasp on the field, but given the polarizing nature of Juul right now, there might be something interesting and ignored here. After speaking to a few buddies, either they think the idea is really exciting or really dumb. Sometimes this might be a sign of the beginning of an interesting investment thesis. Aromatherapies have been around for a long time with little clinical data though and falls into the homeopathy bucket. But maybe a company like Ripple can design a compelling consumer product to bring these treatments/experiences to customers with the value prop of improving health not hurting it.

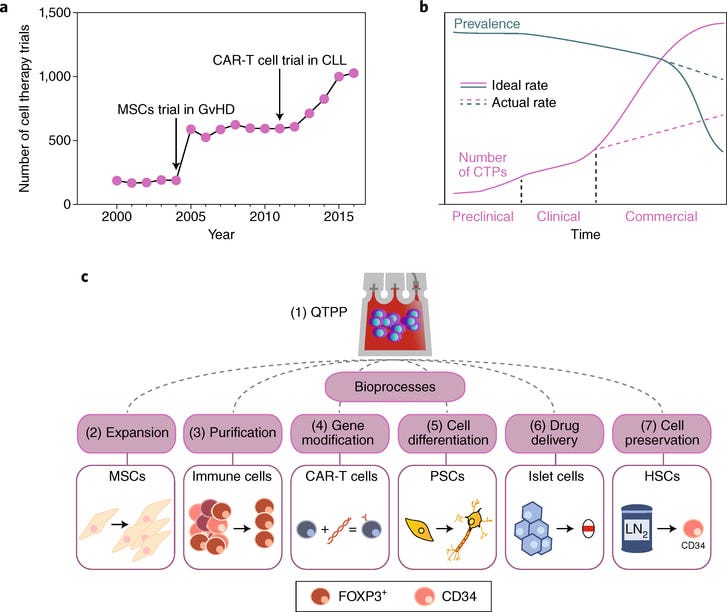

Cell therapy manufacturing

After analyzing quite a few cell therapy companies and then going through all of the old 10-Ks and presentations from companies like Juno and Kite, my conviction on manufacturing being one or probably the limiting factor for overall market success. I collected data on all of the cell therapy companies and matched patients recruited and dosed to market value. Right now, if you can get your cell therapy into ~20 people, your company is probably worth a billion dollars. Being able to scale up production and have a competitive cost structure is a major driver for value creation.

The field is at maybe ~$100Ks per dose and getting to $10K would be transformational. On top of that, these cells therapies have a lot of variance per bag limiting efficacy and safety. There are a functions in cell therapy manufacturing that needed to be backed to make sure patients can get these medicines:

Transformation / Gene modification

Expansion

Sorting / Purification

Cell differentiation

Drug delivery

Cell preservation

All of these functions can be companies. The key levers are decreasing manufacturing cost and time and improving efficacy/safety profiles through less variability, selected receptors combos, defined mixtures, less exhaustion, and a few more. This thesis is true for biologics, AAVs, peptides, and new modalities. There’s a lot of opportunity out there to solve new problems.